JACOB LEISCHNER’21 wrote this article for the Fall 2020 edition of the Inland Empire Outlook

The right to vote, and have that vote heard, is one of the most fundamental principles of the American republic. Every ten years – following the decennial census – states engage in the process of redistricting, where new district lines are drawn in accordance with newly apportioned congressional seats. As redistricting has such a significant impact on one of our most important rights the subject has naturally come before the Supreme Court a number of times, most recently in 2018 in Benisek v. Lamone. Redistricting cases turn on complex questions involving separation of powers, line-drawing responsibility, partisanship, race, or a combination of these and other factors. While an exhaustive review of all Supreme Court cases on redistricting is beyond the scope of this article, it will review a number of important cases to illustrate how the law on redistricting has developed. This article will first discuss some of the earliest Supreme Court rulings considering redistricting and trace the development of the bedrock doctrine of “one person, one vote.” It will then examine the most significant redistricting cases where the central question revolved around population, race, independent commissions, or partisanship. Finally, this article will conclude with a brief discussion of the most recent cases that have come before the Court.

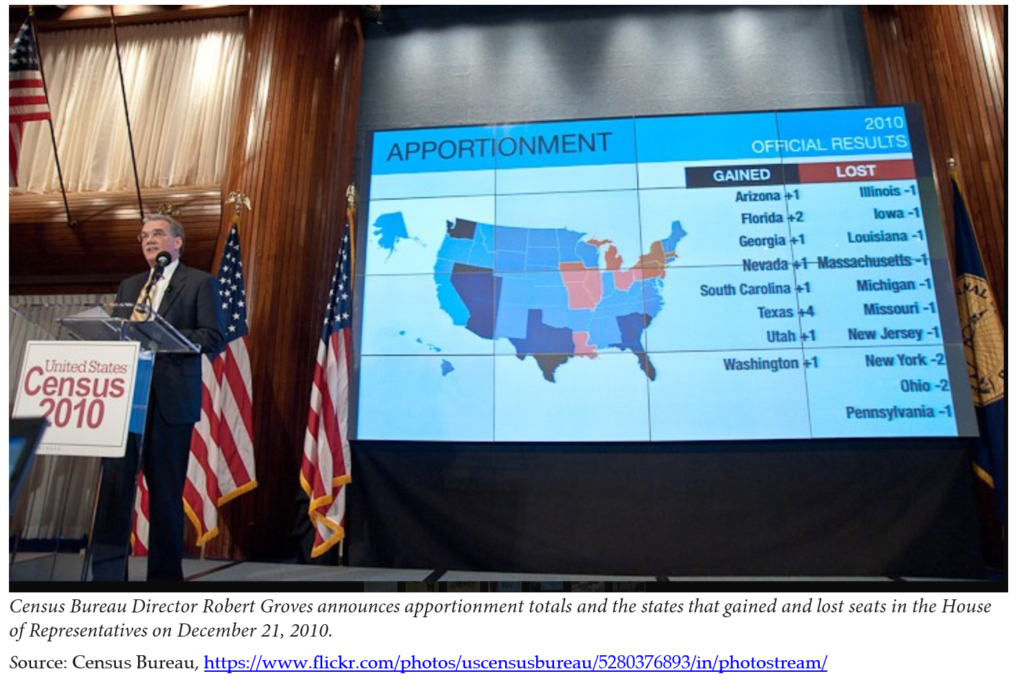

Article 1, Section 2 of the United States Constitution outlines the requirement that Congressional seats “be apportioned among the several States…according to their respective” populations as determined by the most recent decennial census. Each state, once their number of seats has been determined, is then responsible for redrawing their own legislative and congressional districts. Traditionally, this allowed state legislatures (and thus, the majority party in the legislatures at the time of the census) to have nearly indiscriminate control over district boundaries. As time progressed, the country’s demographics shifted with large swaths of the population migrating from rural towns to emerging cities. Despite this population shift, states routinely failed to reapportion seats, resulting in districts with vastly uneven political influence.

Illinois was a prime example of this phenomenon. In 1946, the Supreme Court heard – for the first time – arguments challenging and defending the constitutionality of district lines in Colegrove v. Green. At the time of argument, Illinois had failed to reapportion its districts since 1901 despite significant internal migration. The petitioners were seeking to enjoin the upcoming election until Illinois had redistricted their boundaries. The Court, however, spurned involvement, holding that apportionment was a political question where the actual “remedy for unfairness in districting is to secure State legislatures that will apportion properly or to invoke the ample powers of Congress.”

It was with this precedent – that apportionment was outside the Court’s jurisdiction – that the Supreme Court heard Baker v. Carr in 1962. The Tennessee General Assembly had similarly neglected to redraw their district boundaries since 1901, despite five intervening census cycles in which they were expected to do so (there was no reapportionment following the 1920 census due to debate and eventual passage of the Reapportionment Act of 1929). Additionally, by 1960 an individual vote in one of Tennessee’s smaller rural counties was equivalent to 19 votes in one of the state’s larger urban counties. While the Baker v. Carr case bore many similarities to its predecessor, the decision effectively overturned Colegrove. In a 6-2 decision, the Court established the justiciability of constitutional challenges to state reapportionment, based on the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

This decision, affirming the role of judicial review over the redistricting process, had far-reaching consequences. Most tangibly, within the two years following Baker 26 states redrew their district lines, and by 1966 (only four years after the decision) judicial pressure helped increase that number to 46 states. Moreover, Baker helped lay the groundwork for the later establishment of the now ubiquitous “one person, one vote” doctrine.

In fact, it would be only two years later that the doctrine would be adopted and made concrete precedent by the Court in Wesberry v. Sanders. The plaintiffs were citizens of Georgia’s Fifth District. This simple fact of gross malapportionment was enough for the Warren Court to overturn the federal district court’s ruling on the basis that such population incongruence made the question justiciable. The Court held that Congressional districts must be drawn so that “as nearly as is practicable one man’s vote…is worth as much as another’s.” This precedent was not established on the basis of the Equal Protection Clause, but was found to be required by Article 1, Section 2, the Apportionment Clause of the Constitution.

Later that same year, the Court decided Reynolds v. Sims, which only increased the breakneck pace (relatively for the Court) at which the precedent for the justiciability of apportionment cases was being molded. Alabama, similar to Tennessee in Wesberry, had not reapportioned their districts since 1903, despite migration and economic developments that resulted in vastly unequal populations across districts. Alabama’s largest state senate district had 41 times the voter population of the smallest. The plaintiff argued that this unduly diluted the voting power of some and amplified that of others – effectively disenfranchising heavily populated areas in the state. In his decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren agreed, but this time the basis of the Equal Protection Clause. Warren argued that because the right to vote is a “fundamental political right” it is a prerequisite to political participation and the securing of other rights. Thus, allowing substantial differences in the influence of a vote is unconstitutional. While the Court did not require districts to be exactly mathematically even, deviations from substantially equal districts must have a legitimate and overriding state interest, such as compactness or preserving groups of interest.

Later that same year, the Court decided Reynolds v. Sims, which only increased the breakneck pace (relatively for the Court) at which the precedent for the justiciability of apportionment cases was being molded. Alabama, similar to Tennessee in Wesberry, had not reapportioned their districts since 1903, despite migration and economic developments that resulted in vastly unequal populations across districts. Alabama’s largest state senate district had 41 times the voter population of the smallest. The plaintiff argued that this unduly diluted the voting power of some and amplified that of others – effectively disenfranchising heavily populated areas in the state. In his decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren agreed, but this time the basis of the Equal Protection Clause. Warren argued that because the right to vote is a “fundamental political right” it is a prerequisite to political participation and the securing of other rights. Thus, allowing substantial differences in the influence of a vote is unconstitutional. While the Court did not require districts to be exactly mathematically even, deviations from substantially equal districts must have a legitimate and overriding state interest, such as compactness or preserving groups of interest.

These early Supreme Court cases worked in combination to establish the dual precedents of judicial review over reapportionment plans and the “one-person-one-vote” doctrine. While any redistricting case would draw on these principles, later cases had more narrow foci and questions. For analytical clarity, the next sections will group cases by subject matter.

Population

Connecticut voters soon put the Reynolds decision to the test in Gaffney v. Cummings (1973). Following the 1970 census and subsequent line redrawing, Connecticut state senate districts deviated in total population by a factor of 1.81% and Connecticut House districts by 7.83%. Voters again alleged that this deviation violated the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment, but this time the Court did not agree. This case turned on the idea of “political fairness” and which political boundaries could justify “deviations from perfect population equality.” Justice Brennan, in a prescient dissent, worried that the plans rejected and accepted by the Court set an arbitrary threshold of 10% deviation for justiciability. Successive cases vindicated Brennan’s concern with many decisions (such as Chapman v. Meier (1975), Connor v. Finch (1977), and Voinovich v. Quilter (1993)) explicitly following the very rule Brennan feared the Court established implicitly.

A decade later, the Court heard Karcher v. Daggett (1983) and Brennan now found himself in the majority. After the 1980 Census, the outgoing Democratic party majority in New Jersey passed a congressional map that was approved by the also outgoing Democratic governor. While there was only a total deviation of 0.6984% (about 3,674 people) the lines were clearly drawn to preserve and amplify the power of the Democratic party in the state. The majority of the Court delivered three concurring opinions which held that the burden is on challengers of a state plan to show that population differences could have been eliminated. If they can do so, the burden shifts to the state to demonstrate how the “significant variance between districts was necessary to achieve some legitimate state objective.” Brennan outlined these legitimate state objectives (what we now call “traditional redistricting principles”) as compactness, respect for municipal boundaries, preserving the core of prior districts, and avoiding incumbent contests.

Even with the explication of these principles, simple mathematical calculations of population deviations remained an important metric in assessing equality between districts. States – relying on guidance from the Wesberry and Reynolds decisions – almost always calculated a district’s population proportion as a function of their total population, but Evenwel v. Abbott (heard in 2016) challenged this metric. A federal district court had invalidated Texas’ 2011 reapportionment plan on the basis of violations to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The court put forward an interim plan, which was voted on by the state legislature in November 2012, and then was signed into law shortly after. Not long after, some Texas voters challenged the newly adopted interim plan claiming that it violated the Equal Protection Clause and the Court’s “one person, one vote” doctrine because districts were drawn based on total population rather than registered voter population. Thus, the plaintiffs argued that districts had an extreme unconstitutional variance in the number of registered voters each contained. In a unanimous decision (though only a six-justice majority opinion), Justice Ginsburg wrote for the Court that the language in the Fourteenth Amendment, the debates surrounding its passage, and the Court’s use of total population in past decisions allowed total population to be a permissible metric in determining district equity. The Court did not preclude the use of other metrics (such as the count of registered voters) but did not invalidate the use of total population.

Race

Many of the cases analyzed thus far have been brought forward as violations of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Redistricting cases as they relate to racial gerrymandering similarly rely on the Equal Protection Clause, but often ask the Court additional questions hinging on the Voting Rights Act. This was the case with Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) where Black voters in North Carolina challenged the state General Assembly’s redistricting plan for violating Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, the Equal Protection Clause, as well as the Fifteenth Amendment. The challengers argued that the redrawn districts unduly diluted the voting power of the state’s Black citizens. The District Court, in agreement with the plaintiffs, ruled that five of the six districts constituted unlawful discrimination. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the lower court’s decision. Justice William Brennan Jr. wrote in his opinion that the District Court panel of three judges properly analyzed historical voting data to demonstrate that “minority group members constitute[d] a politically cohesive unit” and that the state’s White voters “vote sufficiently as a bloc usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.” This helped the Supreme Court in turn prove that the North Carolina plan placed “politically cohesive groups of black voters” in districts that were all but sure to regularly defeat Black candidates, a violation of the Voting Rights Act.

Only seven years later, North Carolina’s redistricting plans again came under scrutiny in Shaw v. Reno, decided in 1993. Following Thornburg, the North Carolina legislature submitted a new reapportionment plan to the Department of Justice for preclearance. It was rejected by the U.S. Attorney General. North Carolina’s next plan created two districts where Black voters would make up the majority, but one of these districts had a “bizarre” shape with sections “no wider than the interstate road along which it stretched.” A group of North Carolina voters contended that these districts represented unconstitutional racial gerrymandering and thus violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and held that – despite noble intentions to increase representation – the bizarre shape of the districts seemed to go beyond what would be necessary to secure racial balance in the electorate. The Shaw decision is significant for establishing a precedent to strike down redistricting plans that “cannot be explained on grounds other than race.” The Court also established the idea that a district’s “bizarre” shape can be a strong, though not conclusive, an indication of racial gerrymandering.

Only seven years later, North Carolina’s redistricting plans again came under scrutiny in Shaw v. Reno, decided in 1993. Following Thornburg, the North Carolina legislature submitted a new reapportionment plan to the Department of Justice for preclearance. It was rejected by the U.S. Attorney General. North Carolina’s next plan created two districts where Black voters would make up the majority, but one of these districts had a “bizarre” shape with sections “no wider than the interstate road along which it stretched.” A group of North Carolina voters contended that these districts represented unconstitutional racial gerrymandering and thus violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and held that – despite noble intentions to increase representation – the bizarre shape of the districts seemed to go beyond what would be necessary to secure racial balance in the electorate. The Shaw decision is significant for establishing a precedent to strike down redistricting plans that “cannot be explained on grounds other than race.” The Court also established the idea that a district’s “bizarre” shape can be a strong, though not conclusive, an indication of racial gerrymandering.

Despite Shaw’s establishment of a racial gerrymandering doctrine, the application of such a doctrine was unclear and led to the Court deciding Miller v. Johnson in 1995. Subsequent to the 1990 census, Georgia gained an additional congressional seat. Prior to the 1990 census, Georgia had ten districts only one of which had a Black voter majority despite Black citizens making up 27% of the state’s population. With the addition of a new seat (and thus a new district), Georgia was able to create a second majority-Black district. This new district, however, was widely panned as it stretched nearly 6,800 miles without much consideration for the disparate communities it now joined together. Plaintiffs argued that this district was a racial gerrymander, challenging the state’s redistricting efforts as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Clarifying the Shaw rule, the Supreme Court held that a reapportionment map with “irregular borders” could be ample evidence that “race was the overriding and predominant force in the districting determination” – a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. The Court further affirmed that racial gerrymandering claims should be analyzed on a district-by-district basis, not by the entirety of the state, in Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v Alabama in 2015.

Independent Commissions

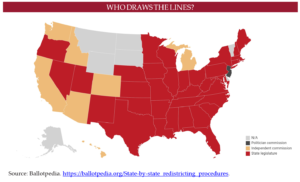

Clearly, there are significant and pressing issues that arise when political actors and bodies are imbued with the power to redraw their own districts. Recognizing these potential pitfalls, a number of states moved redistricting responsibilities to independent commissions. Independent redistricting commissions are either non- or bipartisan, are separate from the political system for which the lines will be used, and are tasked with balancing mathematical equity and traditional redistricting principles. The first state to establish such a commission was Arkansas in 1956 through an amendment to the state constitution proposed and voted on by the state legislature. Currently, 16 states use independent commissions to draw their new district lines or to advise and oversee lawmakers as they draw them.

Clearly, there are significant and pressing issues that arise when political actors and bodies are imbued with the power to redraw their own districts. Recognizing these potential pitfalls, a number of states moved redistricting responsibilities to independent commissions. Independent redistricting commissions are either non- or bipartisan, are separate from the political system for which the lines will be used, and are tasked with balancing mathematical equity and traditional redistricting principles. The first state to establish such a commission was Arkansas in 1956 through an amendment to the state constitution proposed and voted on by the state legislature. Currently, 16 states use independent commissions to draw their new district lines or to advise and oversee lawmakers as they draw them.

In 2000, Arizona voters passed a citizen initiative that created an independent redistricting commission to draw congressional and legislative districts. Fifteen years later, the Arizona Legislature challenged the existence of the commission by defending the idea that only Congress and state legislatures have the constitutional power to redistrict as described in the Elections Clause. In the aptly named Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015), the Supreme Court sided with the commission and voters. It held that “Legislature” in the Elections Clause is not literally applicable when state constitutions have provisions for the people to circumvent it and pass laws directly, as is the case with Arizona’s ballot initiative process.

Partisanship

Many more states, however, do not have independent redistricting commissions and the question of partisan gerrymandering is often raised. Gerrymandering is the act of redrawing political boundaries to favor one party over another and can be a significant concern when incumbents are tasked with drawing their own districts. This was the question before the Court in Davis v. Bandemer (1986), where Indiana Democrats maintained that the legislative lines drawn in the state’s 1981 plan unduly favored the Republican party. The Supreme Court decided two key points: the justiciability of gerrymandering claims and the standard by which to judge such claims. Beginning with justiciability, the Court held that partisan gerrymandering claims were justiciable because there were salient questions of law, not politics alone. However, Justice White in his majority opinion, added the caveat that those challenging redistricting plans on these grounds had to demonstrate the intent to discriminate on the part of the line-drawers. Simply showing discriminatory effect would not be enough to meet this standard.

From Bandemer to 2004 when the Court decided Vieth v. Jubelirer (a period of nearly 20 years), no petitioner was able to demonstrate discriminatory intent in the way Bandemer required. Similarly, no lower court was able to create a manageable alternative standard.

It was with this discourse on precedent that the Court heard arguments for Jubelirer. Following the 2000 census, Pennsylvania was set to lose two Congressional seats. The Republican party (the majority party in the legislature) adopted redrawn lines which would clearly benefit Republican incumbents. A plurality of the Court (a split decision with no majority opinion) held that such partisan gerrymandering claims were not justiciable – overturning the Bandemer standard. Four justices justified their decision on the inability of the 14th Amendment to address questions of partisan gerrymandering, but Kennedy argued that partisan claims could potentially be brought forward under the First Amendment. While this case closed the door on cases looking to overturn politically (though not racially) gerrymandered maps on the basis of “one- person, one-vote,” it offered the hope that a judicial solution could be found eventually.

Recent Decisions

Despite the Court’s ruling in Jubelirer, cases continue to challenge redistricting plans on political grounds. Redrawing district lines inherently involves questions of population, party affiliation, race, and responsibility so redistricting cases will continue to make their way before the Supreme Court. This concluding section will address how current redistricting arrangements reflect the Court’s historical precedent, and then review some of the most recent cases on redistricting.

For the majority of states, lines are redrawn by their respective state legislatures. In fact, only 16 states use independent, nonpartisan commissions – of the type in question in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission – for redistricting. California is one such state. In 2008, California voters approved Proposition 11 (the Voters First Act) which established a redistricting commission comprised of five Democrats, five Republicans, and four non-party-affiliated individuals. The California Citizens Redistricting Commission was responsible for drawing the lines following the 2010 Census.

The number of states relying on commissions may grow this November, with states like Virginia and local governments like Monroe County in New York voting on amendments to require the use of an independent redistricting commission. However, independent commissions are not a one size fits all model. Ohio, for example, utilizes an independent commission but requires a three-fifths majority vote in the legislature with support from at least half of the minority party for a new map to pass. Some states have also opted to not use independent commissions and find other ways to reduce partisanship in the process. Missouri requires a “nonpartisan state demographer” to draft maps, which are then submitted for approval to two nonpartisan commissions, with nominees from each party and the governor having exclusive selection power.

Most recently, the Court heard the landmark case Rucho v. Common Cause and released an equally landmark decision in 2019. Returning to North Carolina, two organizations (Common Cause and the League of Women Voters of North Carolina) filed suit against the state’s 2016 congressional map arguing that it constituted a partisan gerrymander. The district court enjoined the use of the map after November 2018, but its decision was quickly appealed to the Supreme Court. The Court not only was set to consider if the map constituted a partisan gerrymander, but also whether the plaintiffs had standing and whether the claim was judiciable at all. The Court only had to answer one of these three questions. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court held that partisan gerrymandering is a political question that cannot be considered by courts and is thus nonjusticiable. Chief Justice Roberts, in his majority opinion, contended that the framers were aware of the problem of gerrymandering and explicitly imbued state legislatures with reapportionment powers, which are “expressly checked and balanced by the Federal Congress,” not the courts. ¨

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. “About IRC.” n.d. https://azredistricting.org/About-IRC/default.asp.

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, 575 U.S. (2015). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2014/13-895

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission 576 U.S. (2016). Oyez, https://www. oyez.org/cases/2014/13-1314.

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1960/6.

Colegrove v. Green, 328 U.S. 549 (1946). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/328us549.

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1985/84-1244.

Evenwel v. Abbott, 578 U.S. (2016). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2015/14-940.

“Evenwel v. Abbott.” Harvard Law Review. 10 November 2016, https://harvardlawreview.org/2016/11/evenwel-v-abbott/.

Firestone, David. “Hurt in ‘90, Georgia Goes Out for Census.” The New York Times, 15 March 2000. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/03/15/us/hurt-in-90-georgia-goes-out-for-census.html

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1972/71-1476.

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995). Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/1994/94-631.

National Conference of State Legislatures. “Creation of Redistricting Commissions.” August 1, 2020. https:// www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/creation-of-redistricting-commissions.aspx.

National Conference of State Legislatures. “Redistricting and the Supreme Court: The Most Significant Cases.” 25 April 2019. https://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-and-the-supreme-court-the-most-significant-cases.aspx.

Newkirk, Van R. II. “An End to Gerrymandering in Ohio?” The Atlantic, 6 February 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/02/ohio-senate-bipartisan-compromise-redistricting/552413/.

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1963/23.

Rucho v. Common Cause, 588 U.S. (2019). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2018/18-422.

Schneider, Gregory S. “Virginians to vote on proposed amendment for bipartisan redistricting commission.” The Washington Post, 1 October 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/va-politics/virginia-redistricting-amendment-november-ballot/2020/10/01/4b7e0558-0339-11eb-a2db-417cddf4816a_story.html.

Shaw v. Reno. 509 U.S. 630 (1993). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1992/92-357.

The Associated Press. “Number of states using redistricting commissions growing.” 21 March 2019. https://ap-news.com/article/4d2e2aea7e224549af61699e51c955dd.

The Office of Missouri State Auditor. “Nonpartisan State Demographer Applications.” https://auditor.mo.gov/demographerapp.

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1985/83-1968.

United States Constitution. Art. I, Sec. 2.

Vieth v. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267 (2004). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2003/02-1580.

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964). Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1963/22.

Wines, Michael. “What Is Gerrymandering? And How Does it Work?” The New York Times, 27 June 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/27/us/what-is-gerrymandering.html.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.