Written by Manav Kohli ’16

California’s prison population grew by a factor of seven between 1980 and 2006. State prison facilities, however, had not expanded to accommodate the inflow of inmates, and faced severe overcrowding. In 2011 the Supreme Court held in Brown v. Plata that California must reduce its prison population to 137.5% of design capacity. That opinion affirmed the holding of a special three-judge federal court that concluded that the deprivation of adequate medical care to prisoners violated the Eighth Amendment. The Supreme Court agreed with the three-judge panel that overcrowding was the primary cause of the violations and upheld the panel’s order to reduce the state prison population to 137.5% of its design capacity. The Court initially ordered the state to reach that benchmark within two years. However, the three-judge court recently granted California an extension until February 2016 to solve the overcrowding problem.

In response to Brown vs. Plata, California passed Assembly Bill 109, the 2011 Public Safety Realignment Act. In order to reduce the number of inmates in state prisons, AB 109 sought to place more responsibility on the county level. The bill specifically targets offenders whose last crimes were non-violent and non-serious and who are not convicted sex offenders. These inmates are also referred to as ‘triple-non offenders.’ In addition, those who fail to meet the conditions of their parole will also be handled by counties instead of returning to state prisons. However, those offenders who are serving for or have prior serious or violent felonies will remain in the state prison system. AB 109 went into effect on October 1, 2011, and counties across the state have adapted to meet the new burden of integrating offenders into the community and handling them within their own court systems.

In order to implement the changes outlined in the realignment act, each county has created a Community Corrections Partnership (CCP). These committees are charged with allocating state funds to county departments and generally recommending how to integrate the increased number of offenders into the county. Each CCP is comprised of the county chief probation officer, chief of police, the district attorney, the presiding judge of the superior court, and a representative from either the county Department of Social Services, Mental Health, or Alcohol and Substance Abuse Programs, as appointed by the County Board of Supervisors.

Since implementing the 2011 Public Safety Realignment Act, the state has struggled to estimate the correct amount of funding that should be allocated to each county. In the first year of the program, California provided $400 million to support the realignment process, and has increased the budget each year. The following year the state provided counties with $850 million, and increased it further to over $1 billion in fiscal year 2013-14. In 2012 California also passed Proposition 30, which allocated more funds to the California criminal justice system in order to help fund realignment costs.

The California legislature has also passed five bills related to realignment funding. AB 111 gives counties additional flexibility to access funding to increase local jail capacity. AB 94 allows counties to relinquish previous grants for jail facility financing and reapply under a separate financing program and lowers the county’s required contribution from 25% to 10%. AB 118 focuses on the state level to establish the Local Revenue Fund 2011 for realignment financing revenues that will be distributed among counties and directs the deposit of certain sales tax revenues into that account. SB 89 dedicates a portion of the Vehicle License Fee to the Local Revenue Fund 2011. Finally, Senate Bill 87 provides counties with a one-time $25 million appropriation to cover general costs associated with expanding county infrastructure to accommodate the increased number of offenders.

As mandated by AB 109, offenders who have been convicted for felonies, but who did not commit serious, violent, or aggravated white collar crimes and are not sex offenders, are now handled at the county level under the Post Release Community Supervision Departments (PRCS). In addition, offenders who violate their parole are now handled by county probation departments instead of returning to state prisons. The public realignment act changes went into effect in October 2011, and since then all PRCS offenders have been handled at the county instead of the state level.

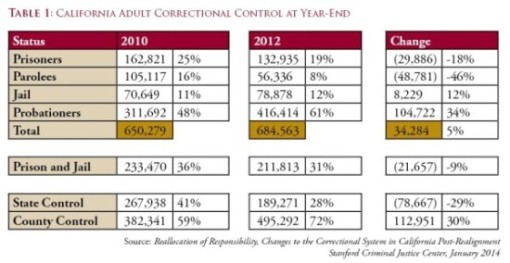

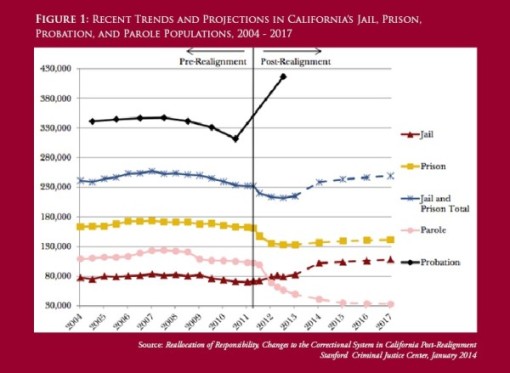

Data from a Stanford study show that realignment is working to shift responsibility for a significant number of prisoners from the state to counties. The number of adults in the 33 state prisons fell from 162,821 in 2010 to 132,935 in 2012, shrinking by 29,886 or 18%. This dramatic drop is largely due to the major diversion of incoming prisoners. Low-level felons who would have been sent to state prison are now sentenced to terms in county jails or placed under other local supervision. In addition, parole violators who used to be returned to state prison are now sent instead to county jails. The number of parolees under state supervision fell from 105,117 in 2010 to 56,336 in 2012. The total number of adults under state correctional control (prisoners and parolees) fell from 267,938 to 189,271 from 2010 to 2012.

The burden placed on counties as a result of realignment is large. In 2010 counties were responsible for 70,649 jail inmates and 311,692 probationers. Together they comprised 59% of all adults in the correctional system in California. That portion has jumped with AB 109’s dramatic shift of correctional control, to 72% in 2012.

The 2011 Public Realignment Act has resulted in many more offenders being handled by county probation departments and other alternative sentencing programs. Probation departments are now responsible for the majority of California’s offenders, 61%, up from 48%. The number of individuals held in jails or prisons fell from 36% to 31% of the total number in the correctional system.

One of the largest concerns with AB 109 is the threat to public safety from integrating more criminals into local communities. Local courts are also motivated to use alternative sentencing measures because of overcrowding within county jails, and many PRCS offenders may enter the community through probation and other programs instead of entering jails. As a result, community members have contact with a larger number of offenders than they would have without realignment measures.

Riverside County

According to the Riverside County’s “Public Safety Realignment & Post-Release Community Supervision Final Implementation Plan,” the Riverside County Community Corrections Partnership Executive Committee Work Group is comprised of seven subcommittees that advise how realignment measures should be funded and implemented. The Fiscal Sub-Work Group oversees accounting procedures and reviews reports regarding how AB 109 funds are being spent by programs and County departments. The Operational Effectiveness Sub-Work Group manages data sharing between the Probation Department, the Department of Public Social Services, and the Sheriff’s Department in order to monitor offenders’ risk to public safety. The Post-Release Accountability and Compliance Team also works to ensure public safety by providing policemen to assist probation officers in compliance checks. The Health and Human Services Sub-Work Group also plays a significant role within the Community Corrections Partnership since it aims to guarantee that all PRCS offenders receive sufficient medical and mental health resources. The Community Corrections Partnership also includes the Day Reporting Center, Measurable Goals, and Court Sub-Work Groups.

Riverside County faced significant troubles beginning the process of integrating triple-non offenders into the community. However, the largest problems arose due to miscalculations in state projections. For example, before October 1, 2011, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation had projected that 1,688 offenders would be transferred from the state to Riverside’s PRCS Department. In fact, as of February 7, 2014, 2,057 offenders had been placed under county supervision, 22% more than the state estimate. Because funding allocations were based on the 2011 estimates, Riverside County received much less than was needed to accommodate the changes outlined in the 2011 Public Safety Realignment Act. The state also miscalculated the number of high-risk offenders that would enter the county, since it only considered the offenders’ most recent crimes in the assessment. After reviewing the criminal records of the inmates who entered the community, the County Corrections Partnership found that 67% were high-risk by state standards, whereas the state estimate was 40%.

By the end of 2011, the Riverside County jail had already reached its maximum capacity, with 3,743 beds occupied. An early prediction of the immediate effects by Steve Thetford, Chief Deputy Sherriff of Riverside County, suggested that there will be an overflow of approximately 480 inmates, 320 of whom can enter alternative sentencing programs, leaving 160 serious offenders outside of prison or a reintegration program. Although that estimate appeared to be accurate in the earliest stages of realignment, it also highlights how the county may be receiving more offenders than it has the resources to deal with, and the potential threat that poses to public safety.

Riverside County was initially provided $21.4 million to implement its realignment plan. However, the county was slow to decide how to spend those funds in a way that would best prepare for the inflow of offenders. At the beginning of the process, the county probation department was one of the few that received concrete allocations to begin implementing changes, and it began by using part of its $6.45 million funds to hire 73 new agents. The Sheriff initially requested $11.6 million, but later agreed to reduce its request by $1 million in order to allocate more resources towards the District Attorney and Public Defender’s offices. The County mental health agency was only awarded $2 million of the $8.4 million it requested.

Just a year after releasing its Final Implementation Plan, the Executive Committee of the Riverside County CCP submitted its “Implementation Plan Update” to the County Board of Supervisors. The report outlines how state funds had been allocated so far, and what measures the county should take moving forward. Between 2011 and 2012, Riverside County received three major allocations from the state. In order to expand its custody, supervision, and treatment services, the county was granted $43,183,181 to its Criminal Justice Alignment/Local Community Corrections Account. This funding partially provided the necessary resources to compensate for the state’s initial underestimate of how many offenders would shift to Riverside County supervision. The CCP also received $200,000 to allocate at its discretion. The District Attorney and Public Defender’s offices have also struggled to accommodate and provide services for the influx of offenders, and the two were granted $344,651 and $852,762, respectively.

Because many Riverside County jails are at full capacity, the County Probation Department has become essential in integrating PRCS offenders into the community. Some measures taken by the county include increased housing options, a Day Reporting Center (similar to what San Bernardino County offers), increased data sharing between offices and county departments, and other partnerships with existing programs. Overall, the county is wrestling with the question of how many offenders it will place in the jail system versus alternative forms of re-entry services.

The Riverside County Sheriff’s Department has seen the most stress in the realignment process since it also has its own jail overcrowding problems. In fact, as of January 1, 2013, almost 25% of the jailed inmates in Riverside County were PRCS offenders. Furthermore, those offenders generally require greater resources and demand higher security, thus placing a larger burden on the judicial system. In order to accommodate more offenders, the Sheriff’s Department has increased its staff and begun to utilize some alternative sentencing programs, such as work release and electronic monitoring. The department has also worked alongside the Department of Mental Health to reintegrate and provide services for offenders. Together, they hope to reduce recidivism by creating opportunities for offenders to gain job skills and access mental and health resources.

Since Riverside County began adapting to realignment, it has significantly expanded its probation department and utilized its Community Corrections Partnership to provide offenders with the resources they need to assimilate back into the community. However, the county will have to work continuously towards providing these resources and expanding its jails in order to accommodate the inflow of triple-non offenders.

San Bernardino County

At the beginning of the realignment process in September 2011, San Bernardino County’s CCP released its “2011 Public Safety Realignment Plan.” According to the report, as of September 1, 2011, San Bernardino County was in charge of supervising 19,000 adult felony offenders. The county approached realignment with the goal of expanding its probation department to accommodate the increased number of offenders. Since San Bernardino County already had extensive rehabilitation programming and a well-organized probation department, it sought to expand its alternative sentencing resources. In fact, it has expanded its three Day Reporting Centers in order to provide more resources for probation, rehabilitation, and treatment services. These centers help offenders assimilate into the community through job training classes and health screenings, among other services. In fact, 59% of all offenders released into the county as a result of the 2011 Public Safety Realignment Act received assistance from some post-release service. According to San Bernardino County Probation Department Spokesman, Chris Condon, the county has seen a decrease in recidivism by over 50% since the beginning of realignment. However, since the realignment process is only in its fourth year, it is hard to predict whether the county will see ongoing reductions.

In addition to providing services through the Day Reporting Centers, the county has also provided funding for its probation department to assist more offenders. The county hired 107 probation officers in 2011, some of whom are stationed in sheriff stations to assist law enforcement agencies. The probation department has also worked to reduce recidivism by providing resources such as evidence-based treatment practices to offenders.

In addition to providing more services and mental and health resources for PRCS offenders, San Bernardino County has also needed to expand its District Attorney’s office. In addition, the Public Defender’s office also immediately sought to hire an extra attorney and more staff to adapt similarly to handling more inmates.

The Adelanto Detention Center has also had to adapt to accommodate the changes mandated by AB 109. According the “2013-2014 Adopted Budget,” San Bernardino County planned to spend $127.5 million on the Adelanto Detention Center Expansion Project, which would double its capacity and add 1,392 jail beds to that detention center. The state committed to provide $88.0 million as part of its County Jail Lease-Revenue Funding Program under AB 900, and would contribute more from its AB 109 growth funds in order to support the necessary increase in staffing. Due to unexpected costs, by January 2014 the county had paid over $30 million in expenses on top of its initial estimate of $91 million. The detention center finally hosted its grand opening in early February, although the final cost of the project was $145.4 million, almost $20 million more than was allocated by the county in its financial report.

The pressure from the inflow of offenders has also caused the county to reduce the amount of jail time for many offenders. California’s criminal sentencing law for felons used to be ‘determinate,’ specifying three possible sentence terms (short, medium, and long) for each crime. Following realignment, judges can now split a determinate sentence between jail time and probation time. In fact, 20% of realignment inmates in San Bernardino County have faced split sentences instead of serving their full time. In contrast, Riverside County has used split sentences for approximately 80% of its PRCS offenders. Although San Bernardino County’s rate is much lower than its neighbor’s, it remains a fact that many offenders in both counties have been put under alternative sentencing measures and are being released early.

Similar to Riverside County, San Bernardino County has also found that many of the offenders transferred from state to county jurisdiction were mistakenly classified as low-risk offenders. In fact, 29% of the PRCS offenders’ earlier convictions were more serious than their most recent one (which is used to categorize them). While the county saw its overall crime rate increase by ten percent, its violent crime rate actually dropped by four percent (the property crimes rate increased by almost nine percent). There has been very little conclusive evidence tying the increased crime rate to the influx of PRCS offenders, and a report released by the Center of Juvenile and Criminal Justice suggested that there has been no proven correlation between a county receiving more PRCS offenders and an increased a higher crime rate.

As demonstrated by its increased use of split sentencing and reliance on alternative sentencing measures, San Bernardino has approached the realignment process by transferring a significant amount of responsibility to the probation department and other community service organizations. Nevertheless, the county has had to significantly expand the Adelanto Detention Center despite its best efforts, and the sheriff’s department is shouldering a much greater amount of work as a result of AB 109. In the coming years San Bernardino County will have to increase its efforts to accommodate the increase in inmates and determine whether the process has a negative effect on public safety.

Both Riverside and San Bernardino Counties have increasingly relied on alternative sentencing measures. In fact, they both have utilized split sentence much more than Los Angeles County, which has only used them in 6% of cases. Proponents of realignment argue that counties can do a better job than the state of managing felons. They argue that now that the responsibility and cost for low-level felons can no longer be thrust upon the state, county officials may have greater incentive to pursue crime deterrence policies.

As counties continue to require more funds from the state for realignment, California officials will have to determine whether the state can sustainably provide the resources necessary for reducing prison populations. Furthermore, as Governor Brown already received an extension to reach the 137.5% goal by February 2016, there will be increasing pressure to provide those necessary funds to county sheriff and probation departments.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.