Written by Daniel Shane ’13

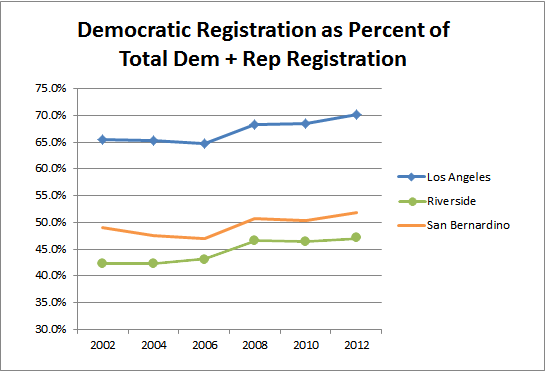

The political landscape in the Inland Empire is turning blue. Once solidly Republican, like Orange County and San Diego, the region’s political shift reflects rapid growth and demographic changes over the past decade. The Inland Empire’s population grew by almost one million between 2000 and 2010 and Latinos made up three-quarters of that growth, a fact that tends to favor Democrats. Democrats’ share of total Democratic and Republican registrants has risen roughly 5 percent in both Los Angeles and Riverside Counties, and almost 3 percent in San Bernardino County in the last decade.

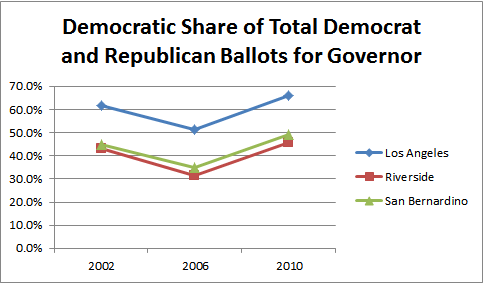

Democratic gubernatorial votes (as a percent of total Democratic and Republican gubernatorial votes) have followed a similar trajectory. Despite a dip between 2002 and 2006 for all three counties, these figures increased just under 5 percent for both Los Angeles and San Bernardino Counties and over 2 percent in Riverside County.

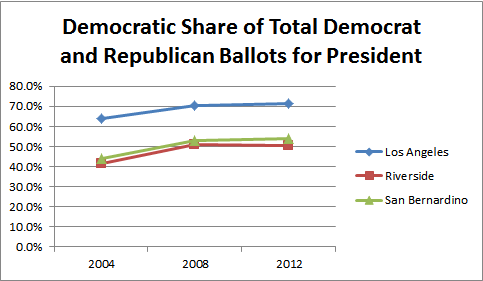

Democrats have enjoyed even more success in recent presidential races. President Obama’s general popularity, coupled with the Inland Empire’s voter registration shift, led to substantial gains for Democrats. In 2004, Kerry earned 64 percent, 42 percent, and 44 percent of total Democratic and Republican votes in Los Angeles, Riverside, and San Bernardino counties, respectively. By 2008, those numbers jumped to 71 percent, 51 percent, and 53 percent for Obama, where they roughly held (72 percent, 51 percent and 54 percent) in 2012.

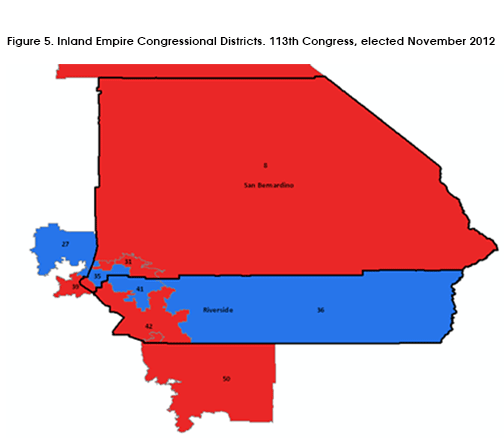

The region’s political shift can also be seen in its congressional delegation and mirrors the change in the California delegation over the course of 30 years. Republicans in 1980 were competitive in congressional districts throughout the state, including many coastal areas. California elected 43 members to the 97th Congress, with Democrats winning a narrow majority (22 vs. 21 seats). Republicans won 14 of their 21 seats in coastal counties. By contrast, only five Republicans elected in 1980 represented districts exclusively in the inland region. Three decades later, the state’s political map had greatly changed. Starting with Bill Clinton’s first election in 1992, Democratic candidates decisively won California’s vote for president. After 1994, they won almost all other statewide elections for U.S. Senate and state constitutional offices (with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s two elections as governor the most important exceptions). After the mid-1990s, they progressively tightened their grip on the state Assembly, state Senate, and congressional delegation until, in 2012, they won two-thirds majorities in all three. In contrast to the evenly divided congressional delegation of 1980 (22 Democrats, 21 Republicans), the delegation elected in 2012 (53 members) is dominated by Democrats, 38-15.

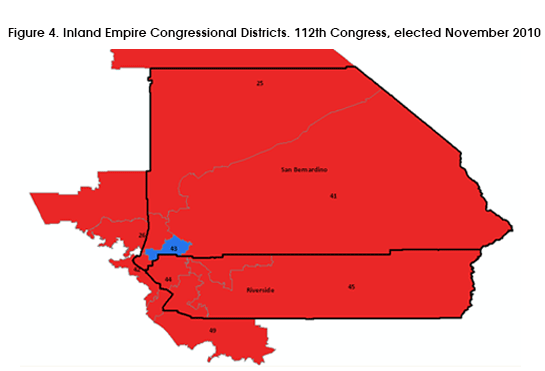

For much of this period, as Republican strength was eroding on the coast, it was concentrating inland, to the point where a majority of Republican districts fell partly or entirely in the inland region. These changes created within California a prominent east-west divide that in many ways replicated the national division of liberal “blue” states on the coasts and the upper Midwest from the conservative “red” states in much of the interior west, lower Midwest, and South. To be sure, just like the national red vs. blue divide, California’s new east-west alignment has exceptions. For example, Republican strength in the inland region was limited by the growth of the Democratic-leaning Latino population, especially in parts of Imperial County, the Inland Empire, and the Central Valley.

Indeed, in the 2012 election, Democrats made new electoral inroads in the state’s interior by winning several closely contested elections in newly drawn legislative districts. For example, in the Inland Empire’s 36th congressional district in Riverside County, Democrat Paul Ruiz defeated six-term incumbent Republican Mary Bono Mack and in the newly drawn 41st congressional district, also in Riverside County, Democrat Mark Takano defeated Republican John Tavaglione. Some areas in San Bernardino County formerly represented by Republicans David Dreier and Jerry Lewis shifted to Democratic control in the new 27th district represented by Judy Chu and the new 35th districted represented by Gloria Negrete McLeod. (See Figures 4 and 5).

The Inland Empire’s voting patterns on statewide initiatives have mirrored the trends in registration and voting for executive office and Congress. While exact statistics are difficult to compare – initiatives do not always align precisely with partisan platforms – one can gauge large-scale shifts in voting patterns by looking at data on initiatives that best correspond to particular parties. For instance, the 2012 Proposition 36 revised the “Three Strikes Law” to allow the imposition of a 25-years-to-life sentence only when the third strike is serious or violent. Like most initiatives believed to relax criminal penalties, Prop 36 was considered to closely align with the Democratic platform. In contrast, Proposition 8 in 2008, which amended the state constitution to declare that only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California, better corresponds with the Republican platform.

Professor Ken Miller, of the Government Department at Claremont McKenna College, analyzed voting patterns on key initiatives in the last twenty years to identify a surge in Democratic voting in the Inland Empire. He identifies five propositions that can be considered as particularly conservative, meaning that the traditional Democratic vote would have been against these initiatives. They are Proposition 187 in 1994, which restricted illegal immigrants’ eligibility for public services; Proposition 209 in 1996, which restricted the use of racial or gender preferences in state contracting, hiring, and university admissions; Proposition 22 in 2000, which adopted a statute that only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California; Proposition 8 in 2008; and Proposition 36 in 2012. It is useful to track the growth of the traditional Democratic positions over the almost two decades that span this group of initiatives. In 1994, only 44 percent of Los Angeles County, 29 percent of Riverside County, and 31 percent of San Bernardino County voted in accordance with the traditional Democratic position on Proposition 187. Six years later, those numbers dropped further to 42 percent, 27 percent, and 25 percent, respectively, on Proposition 22. In 2008, however, signs of a shift emerged. Roughly 50 percent of Los Angeles County votes on Proposition 8 reflected the traditional Democratic vote, as did 35 percent of those in Riverside County and 33 percent in San Bernardino County. While this past election cycle did not feature a clear-cut conservative initiative, the Inland Empire demonstrated more support for two key liberal-leaning initiatives than in the past. Although it did not pass, Proposition 34, which aimed to repeal the death penalty, earned 55 percent of the vote in Los Angeles County, 38 percent in Riverside County, and 39 percent in San Bernardino County – a far cry from the level of opposition in these counties when the death penalty was instituted in California. Proposition 17, which established California as a death penalty state in 1972, saw only 33 percent of Los Angeles County, 27 percent in Riverside County, and 26 percent in San Bernardino County take the Democratic position and vote against the measure. Support for Proposition 36, relaxing California’s “Three Strikes Law,” was even stronger. It was supported by an overwhelming majority of voters in all three counties: 72 percent in Los Angeles County, 62 percent in San Bernardino County, and 64 percent in Riverside County.

Like California in recent decades, the Inland Empire has also become much more densely-populated and diverse. This has had dramatic political consequences. By appealing to an expanding coalition of racial and ethnic minorities and liberal whites, Democrats are extending their near-total control of the heavily populated coastal region into the Inland Empire. Of course, few things in politics are permanent, but for now, the Inland Empire is starting to look blue.

(This article was published in the Inland Empire Outlook: Volume IV | Issue 1 | Spring 2013)

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.