Written by Jessica Jin ’16

Over the past few decades, redevelopment agencies have operated as an influential and powerful conduit for California’s local governments to improve areas in need of economic growth. Originally authorized by the California State Legislature in 1945, redevelopment agencies were first conceived as a local tool to address regional economic issues. The legislation allowed for local agencies to declare certain areas as ‘blighted.’ Through tax increment financing, redevelopment agencies were then provided funding to oversee projects to make local improvements and stimulate economic growth. Tax increment financing is a method of financing that first fixes an initial level of property tax revenue and then allocates any growth to a designated agency.

As the program grew over the years, its scope and power expanded significantly. In 1966 there were only 27 project areas under the supervision of redevelopment agencies (RDAs) with no one area greater than 200 acres, commanding a small portion of the state’s total property tax revenue. In stark contrast, by 2008 RDAs received 12 percent of California’s total property tax revenue—roughly $5.7 billion—and six project areas themselves exceeded 20,000 acres. The expansive RDA program came to a halt on February 1, 2012, when California eliminated redevelopment authorities.

Despite attempts to constrain the use of RDAs in the 1980s, the state legislature failed to curb their rapid adoption and growth. However, sentiment opposing the use of redevelopment agencies grew as RDAs strayed further from an original model that sought to emphasize small-scale regional economic development. In 2010, redevelopment agencies commanded a $5 billion budget across the state of California and not only had minimal voter accountability but also had little to no transparency in their day-to-day operations. The tremendous amount of tax revenue that was redirected towards RDAs revealed the costly price of redevelopment for California. Redevelopment agencies received more property taxes in 2011 than all of the state’s fire, parks, and other special districts combined, and in some areas RDAs received more than the city or county that created them, effectively forcing the state to backfill K-13 districts with a sum equivalent to the cost to fund the University of California or California State systems.

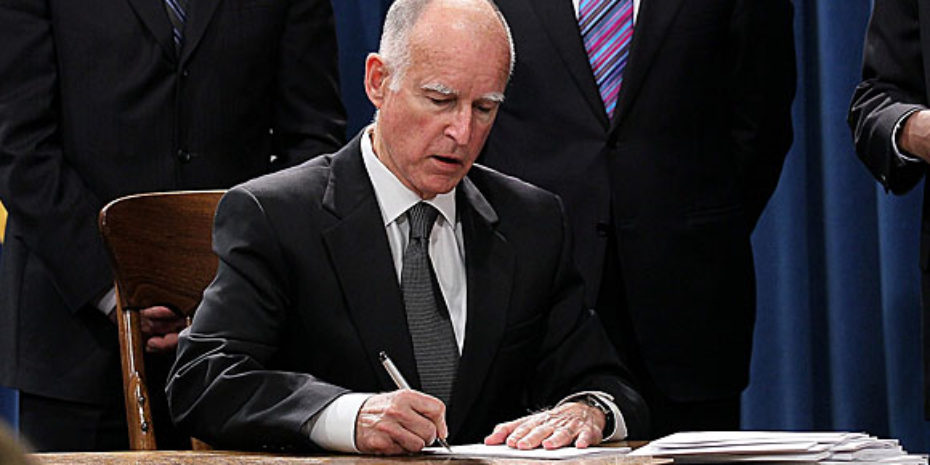

Laws enacted in 1976 and 1993 required RDAs to spend 20 percent of their tax increment funding on affordable housing and required some “pass-through” payments to local agencies that failed to receive any benefits from increase in revenues. Nevertheless, the public still had few methods to monitor an agency’s activities and no state authority audited or monitored a RDA’s actions. Proponents of redevelopment claimed that redevelopment agencies served as efficient and sustainable models to promote economic growth in underdeveloped areas and provided one of the largest funding sources for affordable housing. However, the huge revenue that redevelopment commanded and the money it redirected from other public agencies proved to be the greatest point of contention, spurring Governor Jerry Brown to back legislation to recover portions of the revenue redirected to RDAs.

In June 2011, Governor Brown signed Assembly Bill 26 and Assembly Bill 27 into law. Under AB 26, all redevelopment agencies were directed to immediately suspend the majority of their prior functions such as making loans, incurring new debt, and entering contracts. AB 26 also called for the termination of RDAs by establishing a formal dissolution process to settle financial affairs. Alternatively, AB 27 provided RDAs the opportunity to avoid dissolution if they entered into a voluntary program which included annual payments to other taxing entities such as schools or special districts. Assembly Bill 27 sought to provide a method for RDAs to exist within the current system yet also alleviate some of the burden that the redirected tax revenue cost the state of California in other agencies such as K-13 Districts.

Both AB 26 and AB 27 were challenged in state court. On December 29, 2011, the California Supreme Court upheld AB 26 on the grounds that the California State Legislature had the authority to dissolve entities that it created; however the ruling of California Redevelopment Association v. Ana Matosantos declared AB 27 to be unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated a state provision which prohibited specifying RDAs to transfer funds to particular state agencies. Ironically, the RDAs’ attempt to challenge the legislation which limited but still allowed for their existence proved to be the act that disbanded redevelopment in California in its entirety, leaving AB 27 invalid and forcing RDA dissolution through AB 26.

February 1, 2012 marked the official conclusion to California’s RDA program. The dissolution process set into motion by AB 26 took effect, a process which sought not only to ensure that a redevelopment agency’s existing financial obligations were fulfilled but also sought to minimize any outstanding obligations in order to maximize the remaining funds available for other governmental purposes. In order to do this, the state outlined four key components to the dissolution process: local management and oversight, a comprehensive list of all future redevelopment expenditures, local distribution of funds, and state review.

To achieve this, the state defined successor agencies to manage redevelopment projects currently underway and dispose of assets and properties as advised by an oversight board. Each city or county that created an RDA became its successor agency, except for the following cities that designated their own unique successor agencies: Bishop, Los Angeles, Los Baños, Merced, Pismo Beach, Riverbank, and Santa Paula. Recognizing the administrative costs involved in the transition out of RDAs, successor agencies are allocated up to $250,000, or up to 5 percent of the former tax increment revenues, for administrative expenses in 2011-12 and up to 3 percent in future years. As an advisory panel for the successor agency, the oversight board oversees the successor agency. It is comprised of seven representatives from the local agencies that serve the redevelopment project area: the city, county, special districts, and K-14 educational agencies. Not only does the oversight board approve the successor agency’s administrative budget, but perhaps most importantly, it adopts the ROPS—Recognized Obligation Payment Schedule—the key document that outlines the financial obligations of the former redevelopment agency for which its successor agency is responsible over the next six months. In its advisory role, the oversight board may also direct the successor agency to dispose of assets and properties or to end agreements that don’t qualify as enforceable obligations as it sees fit.

The formal dissolution of redevelopment agencies has been effective for only a year, so the lingering presence of the decades-old program can still be felt in the local governments where they were once so prominent. As cities and counties serving as successor agencies are forced to settle the accounts, the millions of dollars that once were directed into the books of their redevelopment agencies have now become points of contention with the state. The California Department of Finance approved nearly three quarters of the ROPS, which served as expense requests for the successor agencies—predominantly cities—fulfilling the remaining contractual responsibilities of their former redevelopment agencies.

However, out of the remaining quarter, as of late February there have already been nearly 50 law suits filed against the California Department of Finance by individual successor agencies, including a suit filed by the League of California Cities on behalf of several cities. The majority of the suits lie in disputes over what the Department of Finance defines as an enforceable obligation within a ROPS, as opposed to what obligations a successor agency views as enforceable. While successor agencies hold vested interests in completing pre-existing projects in their regions, the Department of Finance instead seeks to move the dissolution of RDAs forward as quickly as possible in order to free tax increment funds for other purposes.

In an earlier attempt to reconcile such disputes, the California Legislature passed Assembly Bill 1484 on June 27, 2012 to make several key amendments to AB 26. Specifically, AB 1484 outlined three new payments for successor agencies and associated penalties if they failed to meet those payment deadlines. The California Department of Finance was also given much greater authority under AB 1484 through the power of the due diligence reviews and findings of completion that it must conduct in order to evaluate successor agencies’ actions and proposals. These measures, however, only proved to exacerbate existing disagreements and ultimately led to the current litigation involving over 50 jurisdictions.

However, despite these legal disputes over funds, these successor agencies currently only serve as transition entities to settle redevelopment debts. It still remains to be seen what measures local communities will take in order to fill the role that RDAs served as providers of affordable housing and drivers of local job growth. Seth Merewitz, a partner at Best Best & Krieger who leads the firm’s Public-Private Partnership/Joint Venture Group, suggests that an effective solution to redevelopment agencies is the adoption and use of public-private partnerships. P3s, as they are also known, seek to resolve issues through the convergence and collaboration of both the public and private sectors. In this, they are similar to RDAs. Where redevelopment agencies funneled public funds into public or private projects, P3s explore the potential of investing private funds in the very same principle.

However, despite these legal disputes over funds, these successor agencies currently only serve as transition entities to settle redevelopment debts. It still remains to be seen what measures local communities will take in order to fill the role that RDAs served as providers of affordable housing and drivers of local job growth. Seth Merewitz, a partner at Best Best & Krieger who leads the firm’s Public-Private Partnership/Joint Venture Group, suggests that an effective solution to redevelopment agencies is the adoption and use of public-private partnerships. P3s, as they are also known, seek to resolve issues through the convergence and collaboration of both the public and private sectors. In this, they are similar to RDAs. Where redevelopment agencies funneled public funds into public or private projects, P3s explore the potential of investing private funds in the very same principle.

As Merewitz notes, “Public investment in local infrastructure will promote private investment. In many communities, existing roads, water, and sewage systems are inadequate to serve new developments. Updating local infrastructure would help with the higher costs of operation and maintenance in urban areas. If the state is serious about infill development, it should invest in local infrastructure and foster community-based financing, not project-based funding.”

The coming years serve as a critical juncture in establishing the future of development projects in California. As successor agencies effectively begin selling off former redevelopment agencies’ assets, the government and private sector should work together to reinvest successfully in such holdings to move local economic development forward. Returning to the original idea behind redevelopment agencies—local economic stimulus in order to promote local development—it is key that local governments partner with local businesses to achieve common goals.

Redevelopment as it once was practiced has ended. However, the goals animating RDAs still have a place in California’s economic development future. Despite the current conflict and complications surrounding dissolution, it is paramount that communities look forward and begin considering measures to replace the roles that RDAs served. Public-private partnerships are only one piece of a greater scheme that not only involves the evaluation of current laws and practices, but also a commitment to establishing new, creative funding sources. In its time, redevelopment’s tax increment financing proved to be revolutionary. Moving forward, it is time, once again, to innovate in order to encourage urban development.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.