by Richard Mancuso ’16

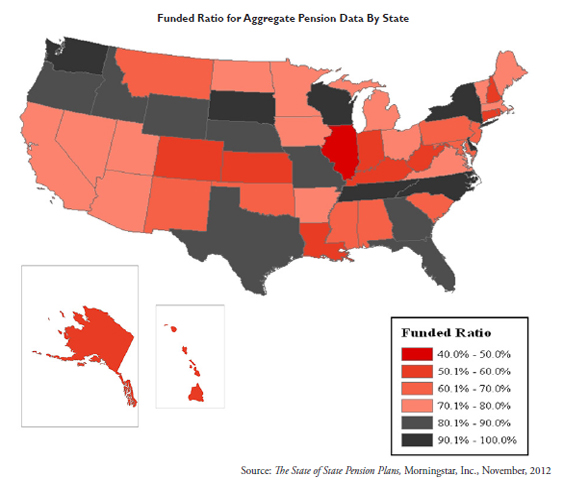

The declaration of bankruptcy by cities like Detroit and San Bernardino has brought renewed attention to the issue of unfunded pension liabilities and the role they play in the fate of local governments. CNBC reports that at least 34 states failed to contribute the necessary amounts to fulfill promised pensions in the past year. The New York Times reports that state and local government pensions are collectively underfunded by at least $1 trillion, likely more. The Times reports that Detroit has nearly $18 billion in liabilities and the state of Illinois has around $133 billion in net pension liabilities. Estimates indicate that Illinois’ net public-employee pension liabilities amount to 241 percent of the state’s annual revenue. In Connecticut it is 190 percent, 137 percent in New Jersey and 17 percent in New York. The growing wave of unfunded pension liabilities must be addressed. There are a number of potential solutions, but first, it is important to examine the initial causes and effects of this crisis.

A pension liability consists of the financial liability incurred through the promise of future pension payments. Specifically, it is the difference between the amount of money due via pensions and the amount of cash the government entity has on hand. Pension liabilities are often labeled as ‘unfunded,’ meaning that the financial resources necessary to fund pension obligations are not sufficient. This usually happens for one or two reasons: either the entity which promised the pension is not able to set aside the necessary funds in the first place or it has diverted funds previously allocated to fund pension liabilities to fulfill another short-term purpose. The problem with the former is apparent, while the problem with the latter is that an entity that today takes a loan from its pension fund, is not likely to be able to repay, plus interest, years down the road when it needs to write pension checks to retiring employees.

The financial crisis and economic downturn in 2008 amplified the adverse effects on the amount of unfunded pension liabilities in municipalities across the country. Many entities, both public and private, invest pension funds in the hope of gaining large returns or, at a minimum, interest. Much like private investments, pension funds suffered significant losses in the financial crisis of 2008. This meant that even municipalities, which had until then adequate financial resources to fulfill promised pensions, were suddenly left short of necessary funds. Although certainly not the only cause, the economic downturn was one key factor in brewing the perfect storm.

In addition to the extraordinary circumstance of the largest financial downturn since the Great Depression, other, more controllable circumstances also played an essential role in leveraging governments across the country. First, public employees were promised very large pensions that required very little personal contribution. According to the New York Times, there are 20,000 public employees in California who receive annual pensions greater than $100,000. Similarly, Chicago pays $1 billion per year solely to retired teachers, and New York City’s pension costs grew from $1.8 billion to $8 billion in a little over a decade. Public officials simply failed to consider the long-term ramifications of offering such large, one-sided pension programs.

Second, a number of government entities spent funds designated for pensions payments on other projects or risky investments with the promise of replacing the spent funds at a later date with new revenue or returns from their investments. Most often, the funds were not replenished, leaving less money to pay out costly pension benefits. For example, The Dallas Morning News reported that the Dallas police-fire pension fund has over $400 million tied up in luxury real estate, from vineyards in Napa to 42-story skyscrapers in Downtown Dallas.

Cities and states across the country are now left speeding down a path toward bankruptcy. There are, however, some potential solutions, including increases in taxes and transition to defined contribution plans. Almost all of these are more difficult than bankruptcy, which so far seems to be the best bad option for municipalities dealing with a collection of budgetary woes. A number of notable cities like San Bernardino and Detroit have already filed for bankruptcy protection under Chapter 9, while even more are likely to follow suit.

Detroit is the most recent and, perhaps, most well-known case of municipal bankruptcy. At between $18 and $20 billion, its July 2013 filing for bankruptcy is by far the largest municipal bankruptcy filing in history. The first signs of Detroit’s fate appeared in 2012 when the state of Michigan was granted greater financial oversight of municipal finances, including the opportunity to appoint a committee to review the city’s finances. Governor Rick Snyder appointed Kevyn Orr as the emergency financial manager of Detroit in March 2013, but it was by then too late. The inevitability of Detroit’s bankruptcy had been solidified over the course of many years. The city has long felt the drastic effects of this unfortunate situation. The Wall Street Journal cites a decrease in population by more than 50% from its peak of 2 million, a tripling of unemployment since 2000, a 100% increase in homicide rate, and average police response times of 58 minutes. Furthermore, only 8.7% of police cases are solved.

Recent changes from the Government Accounting Standards Board may result in an even more troubled picture for cities and states. The new accounting rules will require better disclosure on pension costs and also require governments to use more realistic, lower expected rates of returns on their pension assets. Similarly, Moody’s Investor Services recently announced that it is considering increasing the role that pensions play in the calculation of credit ratings for municipalities. A heavier weight on pensions and related debt would adversely impact the ratings of hundreds of cities. It may lead to more pessimistic forecasts as Moody’s reminds pension and debt holders that they have, “enforceable claims on the resources of local governments.” Moody’s has already placed 30 California cities on review for possible ratings downgrades. The cities on the Moody’s list are Azusa, Berkeley, Colma, Downey, Danville, Santa Monica, Sacramento, Fresno, Glendale, Huntington Beach, Inglewood, Long Beach, Los Gatos, Martinez, Monterey, Oakland, Oceanside, Palmdale, Petaluma, Rancho Mirage, Redondo Beach, San Leandro, Santa Ana, Santa Barbara, Santa Clara, Santa Maria, Santa Rosa, Sunnyvale, Torrance, and Woodland.

The city of San Bernardino declared bankruptcy in the summer of 2012. Officials claimed they no longer had the funds necessary for daily city operations, noting that outstanding pension obligations were a primary cause. Most recent reports cite a $46 million deficit in the city. The U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Central District of California ruled on August 28, 2013 that San Bernardino is eligible for bankruptcy protection. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or Calpers, is the city’s biggest creditor. Calpers staunchly opposed the bankruptcy ruling, arguing that it should not be treated like other creditors and instead should be paid in full. Calpers further argues that this ruling sets a bad precedent for municipalities across the country. The fund is contemplating options for appeal.

Riverside County, on the other hand, has a relatively positive position in terms of pension liabilities. Prior to 2012, Riverside was heading down a similar path, but recent reforms to percentage contributions by employees resulted in roughly $100 million per year in savings. Riverside County CEO, Jay Orr, confirmed a total liability of approximately $5 billion, roughly $1 billion of which is unfunded. This means about 80% of pension liabilities in Riverside County are covered. And, although $1 billion is still a large sum of money, in comparison to local governments across the country, Riverside County’s pension system is considered “well-funded.”

When asked how the county was able to accomplish such reforms, CEO Jay Orr remarked, “It was [a] painful [process]…we have six unions whose contracts were staggered, we were not able to reach agreements with them, so we had to impose on all of them.” He explained that these external pressures, including among others pressure from elected officials, made the negotiations particularly difficult. “We ended up having to give [affected] employees an 8% pay raise [to account for the increase in employee pension contributions].” Although the 8% pay raise cost the county more money up front, the long-term savings will amount to about $100 million per year. “In the beginning it cost us a lot of money, but in the long term it will pay off…we were able to keep most people employed, I have about the same number of people now as I did back then, roughly 18,000 [employees],” said Orr.

On the local level, a number of activists and unions are challenging the legality of bankruptcy, and instead, suggesting alternatives. For instance, in Cincinnati, an organization called Cincinnati for Pension Reform is working to place an initiative on the 2013 ballot, which would transition to a defined contribution pension system. Such a system places responsibility for retirement funding on employees rather than employers.

In response, labor unions continue to fight back against such attempts at change. They want to ensure access to promised benefits and ensure the accessibility of such benefits for future employees as well. In the case of Cincinnati, the Ohio Civil Service Employees Association is encouraging public workers not to settle for any sacrifice of employee benefits. Such campaigns leave reforms unlikely to pass via ballot initiative, unless a sudden shift in public opinion occurs.

The United States federal government engaged in a similar transition in the 1980’s in an attempt to make pension liabilities more manageable. At the onset of the 1980’s defined benefit pension plans were most popular amongst federal employees. Since then, defined contribution plans have become an integral part of the Federal Employees Retirement System. The transition occurred in 1986 due to rising costs associated with defined benefit plans and a growing number of government employees who had been granted access to such pension programs. The plan now consists of three parts: a defined benefit plan known as the FERS annuity, mandatory Social Security participation, and a defined contribution plan known as the Thrift Savings Plan.

There are, however, other potential solutions to the municipal pension crisis, namely a number of combinations of tax increases across the board and changes in the nature of current and/or future pension plans.

The first broad alternative is to increase taxes. There are three different potential tiers for increased taxation. The first involves maintenance of the status quo from the standpoint of pension benefits and an increase in household taxes sufficient to cover those costs. Such an option, however, seems unattractive due to the fact that, according to a study done by Robert Novy-Marx of the University of Rochester and Joshua Rauh of Stanford University, it would require an increase in taxation across the board of $1,385 per household per year to pay for the massive amounts of both state and municipal government pension liabilities.

Another slightly more attractive option has municipalities engage in a “soft freeze,” meaning that newly hired employees are enrolled in a defined contribution (as opposed to a defined benefit) system. In a defined contribution retirement plan, employees, not employers, pay into retirement funds. Even with such changes, the same study indicates that an increase in taxation by $1,210 per household per year is necessary.

Finally, the least conservative option from the standpoint of both municipalities and their employees, is a “hard freeze” combined with an increase in taxation across the board. A “hard freeze” would entail the halting of employer benefit contributions for all employees, regardless of tenure, in addition to the enrollment of newly hired employees in a defined contribution system. Novy-Marx and Rauh indicate that such measures would still require annual tax increases of $700-$800, per household. Although effective, such plans face an uphill battle given the political cost from public employees and taxpayers. This leaves municipal governments with just one more option: the status quo (and likely bankruptcy), bringing us back to square one.

Bankruptcy offers local governments a process – albeit lengthy and complicated – to deal with creditors and discharge financial obligations. It offers little solace, however, to the public employee who will likely lose some or all of her promised pension or to the taxpayer who will pay for the government’s mistakes over the course of many decades.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.