The Impact of Proposition 15’s Revision on the Property Taxes of Shopping Malls in Los Angeles County

by Marshall Bessey ’23

With research assistance from Naseem Nazari ’21

Background

During the 1970s in California, rising property prices saddled homeowners with increasing property tax bills. By the tax year of 1977-1978, property taxes in California were fifty-two percent greater than the national norm, and its per capita burden from all state and local taxes was the third highest out of all fifty states.[1] In response to this high tax burden, Howard Jarvis, a businessman from Los Angeles, partnered with Paul Gann, a conservative activist from Sacramento, to sponsor Proposition 13. Proposition 13 proposed freezing property taxes based on their assessed value in 1975-76 and limiting yearly increases to two percent unless the property was sold. Once sold, the property would receive a reassessment at one percent of the sale price with yearly increases still capped at two percent. Proposition 13 also required a two-thirds majority in each house of the California Legislature to approve any new proposed tax revenue increase and approval from two-thirds of voters for any new “special” local tax.[2] Proposition 13 passed with 65 percent of the vote and became part of the California Constitution.[3]

In 2000, voters amended Proposition 13 with Proposition 39, requiring only 55 percent of local voters to approve a tax revenue increase for school construction.[4] Throughout the years, voters have approved several amendments to Prop 13, but most of the measure’s key provisions remain in place.

When Proposition 13 capped the property tax rate at one percent and limited future property tax increases at two percent per year for homeowners and business properties alike, it shifted the majority of the tax burden to homeowners. In 1975, commercial properties paid 46.6 percent of the total property tax roll while homeowners paid 33.9 percent. By 2010, commercial properties paid only 30.9 percent of the total property tax roll and homeowners paid 55.8 percent.[5]

Some academics have argued that the effects of Proposition 13 are much more consequential than just the tax burden shift produced by the law. In a 2010 article, California in Crisis, Donald Cohen and Peter Dreier argue that Proposition 13 places newer businesses at a competitive disadvantage to older firms. This competitive disadvantage stems from the heavier taxes placed on newer commercial properties.[6] Cohen and Dreier also point out that because homeowners sell their homes more often than businesses sell commercial properties, homeowners pay a much higher tax rate per square foot. Disney, for example, pays a nickel per square foot for its Disneyland property whereas a typical home pays more than two dollars in taxes per square foot.[7]

Other academics argue that the effects of Proposition 13 go much further by constraining the revenues available to local governments and public schools. Overall, about 60 percent of property taxes go to cities, counties, and special districts, with the other 40 percent going to K-12 schools and community colleges. In Loosening Fiscal Straitjackets, Iris J. Lav and Jon Shure contend that Proposition 13 made California’s government fiscally inflexible because limits on property tax revenues force local school districts depend on state aid for their funding.[8]

On the other hand, Proposition 13 has not caused property tax revenues to dry up. Even under Prop 13’s limits, the property tax continues to generate relatively robust revenues for local governments and schools (currently about $65 billion), largely because the state’s property values are so high. According to Zillow’s home value index, the typical home value in California is $586,659—far higher than the national median.[9] Especially as properties are sold and their assessed values reset to market value, the one-percent assessment generates substantial property tax revenues. The Tax Foundation reports that California currently ranks 17th in the nation in per capita property tax collections.[10]

Proponents of Proposition 13 argue that the law creates a fair and predictable property tax system. The Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association notes that property owners know exactly what their property taxes will be in future years.[11] This certainty incentivizes property owners to invest in property in California because they know that future property market trends could not potentially tax them out of this property. Proponents argue that Proposition 13 is a fair system because its rules apply universally to every type of property. Therefore, no specific sectors of California’s real estate market receive preferential treatment by tax assessors.

Proposition 15 would create a split-roll based tax system. Regulations under Proposition 13 would still determine property taxes for homeowners, but the Prop 15 revision would lead to the reassessment of commercial properties if the owner has more than $3 million of commercial land and buildings in California. The reassessment would be based on the current market value. The Legislative Analyst’s Office projects that the split-roll tax system would bring in between $7 billion and $11 billion of additional tax revenue.[12] Forty percent of this money would go towards schools based on California’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The LCFF revised the way California distributed money to school districts intending to equalize the academic results of school districts. The remaining sixty percent of the revenue would go back to local governments.[13] However, organizing support for any revision of Prop 13 may prove a daunting task. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, 65% of likely voters think Proposition 13 is mostly good.[14]

This study examines how Proposition 15 would affect one type of commercial real estate, specifically shopping malls in Los Angeles County. Shopping malls are some of the largest and most valuable pieces of commercial real estate in the county, and are increasingly vulnerable to online competition, making it critical to understand Proposition 15’s impact on them. This project seeks to calculate how much additional tax revenue the government could receive from shopping malls with the goal of a better understanding of how Proposition 15 would affect various segments of the commercial real estate market.

Methodology

To determine how much additional tax revenue Los Angeles County would receive from shopping malls, we first compiled a list of all shopping malls in LA County. The online Los Angeles Almanac provides such a list.[15] We relied on this database of shopping malls because it provided much more additional information than just the names of all the shopping malls. LA Almanac highlighted whether each mall was an outdoor or indoor mall, and the database also shared each mall’s community, address, and year of opening. Next, we took into account the acreage of property using data from Google Earth Pro, then relied on Zillow’s free public database of current property listings to determine the value of land in a given area. For most properties, Zillow provides a Zestimate, Zillow’s estimate of the property’s market value. In cases without a Zestimate, the study relied on the listing price to determine the estimate of the market value per acre for that particular mall. Those estimates may not be as accurate as the estimates based on properties with Zestimates.

We used this data to determine the approximate market value for each shopping mall in Los Angeles County. Then, we took one percent of this figure to determine the one percent property tax rate for each property. We decided to take the one percent property tax rate for each shopping mall because it is the only property tax that applies to every property across California. Once this was done for all of the shopping malls in Los Angeles County, we determined the sum of the estimated tax revenue from each shopping mall. Once all the estimated property tax revenues had been calculated, we used the LA County Tax Assessor’s database to determine the 2020 assessed value for each of the properties. Once all the data has been collected from the Tax Assessor’s Database, we determined the sum of the tax revenue from each shopping mall.

This study collected data on the thirty-two malls listed in the online Los Angeles Almanac.[16] It did not collect data on strip malls or other major shopping centers.

Limitations

When searching the LA Tax Assessor’s database, we found that some of the property tax bills for shopping malls were incredibly low. One possible explanation for this issue with the dataset is that some shopping malls span multiple addresses and so it would be necessary to find the property tax bill for each address individually. Another issue is that the Los Angeles County Tax Assessor’s database is not fully updated. We could not find updated assessed values for Panorama Mall, Century City Westfield or Manhattan Village, and two other shopping malls. Without this information, the study could not determine the property tax bill for these malls under Proposition 13. Therefore, this study did not estimate market values for those five malls.

One significant limitation of relying on Zillow’s database of current property listings is the lack of data on previous land sales. In some of the neighborhoods near a shopping mall, there was no land currently listed on Zillow. The lack of nearby listings means that some of these estimates are not as accurate as they could be. Another limitation to Zillow’s database is that it does not have any property listings for shopping malls. Therefore, this study can only estimate how the property taxes from the value of shopping mall land will change due to Proposition 15’s split-roll system. Even though the estimates are not as precise as we would have liked, this data still provides a reasonable estimate of the one percent property taxes from shopping malls if voters pass Proposition 15. One significant limitation of relying on the LA County’s Tax Assessor’s database to determine the property taxes from shopping malls under Proposition 13 is that the database often had multiple differing results for each address. We had to search through these results to figure out which results showed the current and active property assessment.

Another limitation is that this study cannot predict the behaviors of shopping mall owners. It is possible that if Proposition 15 passes, shopping malls will change their policies and behaviors in a way to minimize the change to their tax bill. Under Proposition 8 (passed in 1978), commercial property owners can file an appeal if they believe that the value of their property declined below its assessed value.[17] Businesses could use this appeal process as a way of fighting back against the possible effects of property tax changes proposed under Proposition 15.

Findings

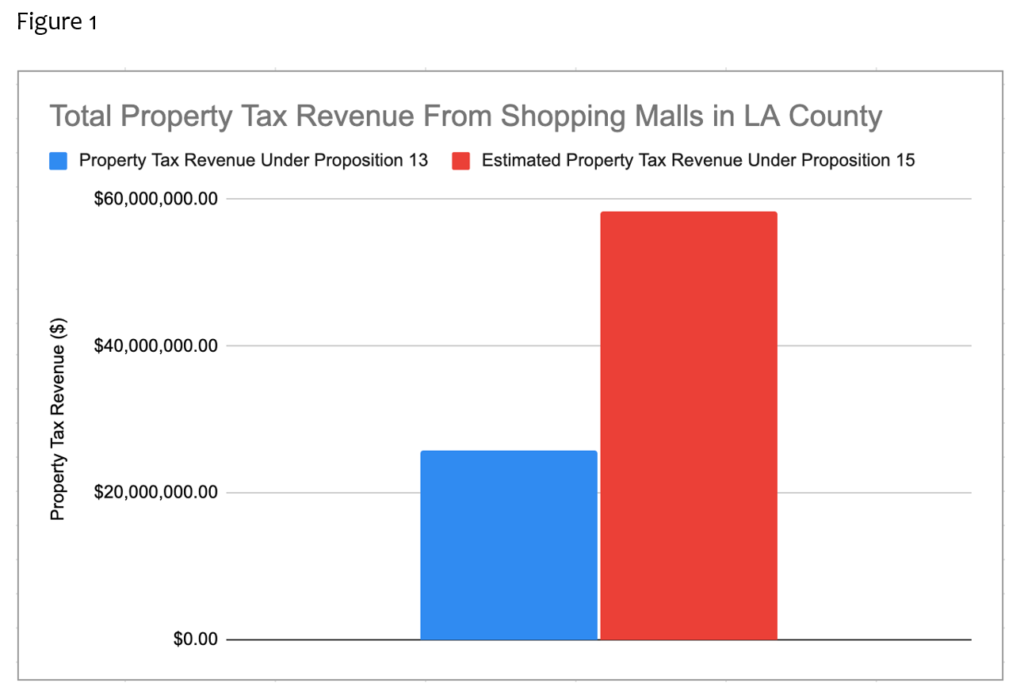

Figure 1 shows the estimated property taxes of the twenty-seven malls in our dataset under Proposition 13 and Proposition 15 respectively. This study found that shopping malls paid around $25,000,000 in property taxes from the one percent rate under Proposition 13. It estimated that these twenty-seven malls would pay around $58,000,000 in property taxes under the universal one percent property tax rate under Proposition 15’s proposed new system. According to these estimates, Proposition 15 would increase LA County’s property tax collection from the twenty-seven shopping malls by nearly 132 percent.

Figure 1 shows the estimated property taxes of the twenty-seven malls in our dataset under Proposition 13 and Proposition 15 respectively. This study found that shopping malls paid around $25,000,000 in property taxes from the one percent rate under Proposition 13. It estimated that these twenty-seven malls would pay around $58,000,000 in property taxes under the universal one percent property tax rate under Proposition 15’s proposed new system. According to these estimates, Proposition 15 would increase LA County’s property tax collection from the twenty-seven shopping malls by nearly 132 percent.

The mean and median figures follow similar patterns. The median shopping mall’s property tax bill under Proposition 13 and Proposition 15 is $640,235 and $1,722,146 respectively. The average property tax bills of shopping malls show the same trend. The mean shopping mall’s property tax bill would go from $952,278 to $2,161,805.

Despite some of the limitations of the data, this study’s findings still highlight the projected property tax revenue boost from shopping malls if Proposition 15 passes. It indicates more broadly that cash-hungry local governments in pandemic California have much to gain if Proposition 15 passes. The flip side, of course, is that businesses, already hurting from COVID and the lockdown, will be in an even tighter financial predicament.

Works Cited

Ballotpedia. “California Proposition 13, Tax Limitations Initiative (1978).” Accessed October 28, 2019. https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_13,_Tax_Limitations_Initiative_(1978).

Ballotpedia. “California Proposition 39, Supermajority of 55% for School Bond Votes (2000).” Accessed October 28, 2019. https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_39,_Supermajority_of_55%25_for_School_Bond_Votes_(2000).

Cohen, Donald and Peter Dreier.“California in Crisis,” American Prospect 21, no. 2 (2010).

Lav, Iris J. and Jon Shore. “Loosening Fiscal Straitjackets.” American Prospect 21, no. 2 (2010).

“League of California Cities – ACA 1 Offers Flexibility for Local Financing of Infrastructure and Affordable Housing.” Accessed October 28, 2019. https://www.cacities.org/Top/News/News-Articles/2019/March/ACA-1-Offers-Flexibility-for-Local-Financing-of-In.

Loughead, Katherine. “Property Taxes Per Capita | State and Local Property Tax Collections.” Tax Foundation (blog), March 13, 2019.

https://taxfoundation.org/property-taxes-per-capita-2019/.

“Major Shopping Malls and Other Shopping Areas of Note in Los Angeles County, California,”

Accessed October 19, 2020, http://www.laalmanac.com/economy/ec15.php.

Marinucci, Carla. “‘Split-Roll’ Backers Will Refile Tax Initiative in Expensive Rewrite.” Politico PRO. Accessed October 29, 2019. https://politi.co/2OQeaGx.

Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association. “Prop. 13 Has Made Everyone’s Property Tax Reasonable.” Accessed October 22, 2020.

Baldassare, Mark, Dean Bonner, Alyssa Dykman, and Lunna Lopes. Public Policy Institute of California. “Proposition 13: 40 Years Later.” https://www.ppic.org/publication/proposition-13-40-years-later/.

Romero, Dennis. “L.A. Country Club Pays Ultra Low Property Tax Rate; Faces Possible Review.” LA Weekly, December 18, 2009. https://www.laweekly.com/l-a-country-club-pays-ultra-low-property-tax-rate-faces-possible-review/.

Sears, David O. and Jack Citrin. Tax Revolt: Something for Nothing in California. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982: 21

“Split-Roll Property Tax Ballot Initiative Revised for 2020 – California Land Title Association.” Accessed October 29, 2019.

https://www.clta.org/news/466288/Split-Roll-Property-Tax-Ballot-Initiative-Revised-for-2020.htm.

“Temporary Decline in Market Value (Proposition 8).” Accessed October 10, 2020.

https://www.sccassessor.org/index.php/tax-savings/tax-reductions/decline-in-value-prop-8-tab.

Zillow, Inc. “California Home Prices & Home Values.” Zillow. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.zillow.com:443/ca/home-values/

[1] David O. Sears and Jack Citrin. Tax Revolt: Something for Nothing in California. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982: 21.

[2] “California Proposition 13, Tax Limitations Initiative (1978),” Ballotpedia, accessed October 28, 2019, https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_13,_Tax_Limitations_Initiative_(1978).

[3]Mark Baldassare, Dean Bonner, Alyssa Dykman, and Lunna Lopes “Proposition 13: 40 Years Later,” Public Policy Institute of California (blog), June 2018, https://www.ppic.org/publication/proposition-13-40-years-later/.

[4] “California Proposition 39, Supermajority of 55% for School Bond Votes (2000),” Ballotpedia, accessed October 28, 2019, https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_39,_Supermajority_of_55%25_for_School_Bond_Votes_(2000).

[5] Donald Cohen and Peter Dreier. “California in Crisis.” American Prospect 21, no. 2 (2010); Dennis Romero, “L.A. Country Club Pays Ultra Low Property Tax Rate; Faces Possible Review,” LA Weekly, December 18, 2009, https://www.laweekly.com/l-a-country-club-pays-ultra-low-property-tax-rate-faces-possible-review/.

[6] Cohen and Dreier,“California in Crisis.”

[7] Ibid.

[8] Iris J. Lav and Jon Shore. “Loosening Fiscal Straitjackets.” American Prospect 21, no. 2 (2010). Lav and Shure further argue that while citizens think that Proposition 13 gives them more control over government, the proposition actually gives them less control, because rigid property tax formulas cannot adapt to changing circumstances.

[9] Zillow Inc, “California Home Prices & Home Values,” Zillow, accessed October 22, 2020, https://www.zillow.com:443/ca/home-values/.

[10] Katherine Loughead, “Property Taxes Per Capita | State and Local Property Tax Collections,” Tax Foundation (blog), March 13, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/property-taxes-per-capita-2019/.

[11] “Prop. 13 Has Made Everyone’s Property Tax Reasonable,” Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, accessed October 22, 2020, https://www.hjta.org/propositions/proposition-13/proposition-13-has-made-everyones-property-tax-reasonable/.

[12] Carla Marinucci, “‘Split-Roll’ Backers Will Refile Tax Initiative in Expensive Rewrite,” Politico, April 2, 2020, https://politi.co/2OQeaGx.

[13] “Split-Roll Property Tax Ballot Initiative Revised for 2020,” California Land Title Association, August 20, 2019, https://www.clta.org/news/466288/Split-Roll-Property-Tax-Ballot-Initiative-Revised-for-2020.htm.

[14] Baldassare, et al., “Proposition 13: 40 Years Later.”

[15] “Major Shopping Malls and Other Shopping Areas of Note in Los Angeles County, California,” accessed October 19, 2020, http://www.laalmanac.com/economy/ec15.php.

[16] “Major Shopping Malls and Other Shopping Areas of Note in Los Angeles County, California,”

[17] “Temporary Decline in Market Value (Proposition 8),” 8, accessed October 10, 2020, https://www.sccassessor.org/index.php/tax-savings/tax-reductions/decline-in-value-prop-8-tab.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.