By Nathan Falk ’14

Southern California is still a few years away from hosting a Super Bowl, but bringing football back to Los Angeles is not as far off as some may think. The National Football League insists that it wants to be back in LA under the right circumstances and two competing groups say they are up to the task. Anschutz Entertainment Group and Majestic Realty Co. have put forward competing proposals for building top of the line stadiums in the LA basin.

Stadium Financing

Each stadium plan is unique, with different political considerations, costs, and construction concerns. Both projects, however, share a hefty price tag, with cost estimates running close to a billion dollars for each project. In order to cover the massive price tags of new sports arenas, many real estate developers partner with local governments to access some public money. For example, the new Yankee Stadium financed $300 million of its $1.5 billion construction cost using bonds and public funds. Similarly, a proposed new arena in Seattle, will finance $200 million of its $450 million construction cost through city and county funds. Typically, a city issues municipal bonds in order to finance new stadium projects. A bond is a debt security. It is a formal contract to repay borrowed money with interest at fixed intervals. Bond financing is the most common mechanism used by government entities to borrow money.

Taxpayers, however, are often wary of assuming the repayment obligations incurred by issuing bonds. Many object to bond financing for projects like stadiums that are rarely profitable. A 1997 study by the Brookings Institute found that cities usually end up having to pay a large portion of stadium costs from public funds or increased taxes. Additionally, citizens and politicians are often loath to tie up valuable and scarce public funds in public-private joint ventures at a time when governments across the board are running deficits. In Seattle, for instance, public outcry has centered on the fact that funds could be better put towards defraying Seattle’s multi-million dollar deficit.

Many modern stadiums and arenas are designed as mixed-use development, coupling the sports aspect of a stadium or arena with retail and commercial spaces. The St. Louis Cardinals’ Busch Field, for instance, is completing work on Ballpark Village that will include everything from restaurants to residential spaces. That being said, these mixed-use developments are not automatic financial successes. The original design for Busch Field Ballpark Village, for instance, has been scaled back 80% due to lower than anticipated demand, and will open in 2013, rather than the planned 2011.

Potential investors like mixed-use developments because they greatly expand a stadium’s revenue streams. Creating these villages allows for a continuous monetization of the space with shops and restaurants open every day, rather than the intermittent usage typical of stadiums.

Another common financing tool is the sale of Personal Seat Licenses, or debentures. Personal Seat Licenses, or PSLs, give ticket holders the rights over specific seats in a stadium. The PSL holder can choose either to renew the license each season, or sell it. PSL holders who fail to do either forfeit their licenses back to the team. PSLs are common and highly lucrative way for venues to recoup many of the sunk costs associated with the construction of the arena.

Personal Seat Licenses have been a great success in the NFL, where 14 of the league’s 32 teams employ them. The licenses often sell for thousands of dollars, and can net a team or venue hundreds of millions of dollars. The new Giants Stadium, for instance, made around $150 million from the sale of PSLs, defraying about 10% of construction costs.

Much of the stadium debate, however, is framed around the question of economic benefits. Studies by the Brookings Institute and the Cato Institute find that stadiums actually end up costing far more money than they bring in, and are indeed just white elephants and points of pride for a city. The Brookings study found that many stadiums claim an annual federal tax loss of over a million dollars.

Indeed, some economists see any family spending on games and events at stadiums and arenas as money that would otherwise have been spent on other forms of entertainment.

They argue that families have an “entertainment budget,” where money that is spent on a game would otherwise have gone into the local economy to pay for movies or local restaurants. Similarly, they argue that hotel taxes may not increase revenue. Taxes collected on hotel rooms is money that out-of-town visitors would otherwise have available to spend at local restaurants, attractions, and on souvenirs.

Proponents argue that mixed-use stadiums could be a simple solution for this issue. Sports by their nature are sporadic and decentralized income generators. Football stadiums, for instance, only make money one day a week, staying empty and incurring heavy maintenance costs for each of the other six days. Even by expanding the stadium’s use to other sports, such as MLS soccer, as in the case of CenturyLink Field in Seattle and Gillette Stadium in Massachusetts, the stadium remains empty on most days of the week.

By expanding the scope of the stadium area to include retail and commercial space, stadiums and arenas can generate revenue every day of the year. Retail stores, residential areas, and concert venues, as anticipated in the St. Louis Ballpark Village, have the potential to generate additional revenues for the stadium and arena owners, as well as additional taxes for state and local governments. This argument assumes that the revenues from these mixed use developments supplement existing local business revenues, rather than replace them.

Proposed LA Stadium Projects

There are currently two competing proposals for NFL stadiums in LA and they could not be more different.

Farmers Field

Farmers Field is the plan put forth by AEG, the same company that developed L.A. Live. The stadium would be located next to Staples Center and L.A. Live at the current Los Angeles convention center. In fact, part of the convention center will have to be torn down and rebuilt to accommodate the design. The $1.1 billion dollar project will be designed by the architectural firm Gensler and will be paid for through a combination of sponsorships and over $200 million in city-issued bonds. The city insists, however, that AEG will be responsible for this debt, and that the developer, not the taxpayer will be assuming most of the costs and risks. The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between AEG and the City of Los Angeles lays out some of the details of this financing. The City of Los Angeles will help cover the cost of the reconstruction of the convention center, and the NFL will help cover the cost of the stadium, hence the group’s claim that no public financing will be used for the stadium itself.

The downtown location has an estimated capacity of 68,000 seats for most events, although that number could be expanded to as much as 78,000 for special events such as the Super Bowl or NCAA Final Four games. Project supporters project some $410 million in new revenue for the city over the next 30 years. They estimate it will likely create between 20,000 and 30,000 new direct and indirect jobs, including everything from construction to stadium operations and added convention center positions. The developer estimates that this 1,700,000 square foot building could be ready for the 2016 football season.

The downtown location has an estimated capacity of 68,000 seats for most events, although that number could be expanded to as much as 78,000 for special events such as the Super Bowl or NCAA Final Four games. Project supporters project some $410 million in new revenue for the city over the next 30 years. They estimate it will likely create between 20,000 and 30,000 new direct and indirect jobs, including everything from construction to stadium operations and added convention center positions. The developer estimates that this 1,700,000 square foot building could be ready for the 2016 football season.

Governor Jerry Brown has been supportive of the AEG proposal. Senate Bill 292, which passed the California legislature this past fall, helps to expedite Farmers Field’s construction. The bill does not provide any exemptions from environmental regulations, but rather limits the length of legal challenges to 175 days. The Senate Bill was passed in conjunction with a more general bill, Assembly Bill 900, which provides these types of benefits to all large “leadership projects” such as stadiums. These provisions are intended to speed up the litigation process and help such projects move forward.

Farmers Field is currently in a state of limbo. Last summer, AEG’s Tim Leiweke was reportedly engaged in talks with five NFL teams. However, the NFL did not make Los Angeles a priority, during the season and has shown little support for the proposal since the Super Bowl. While the AEG team still puts the stadium’s expected opening date at 2016, the lack of progress luring a team suggests that may be optimistic.

Grand Crossing

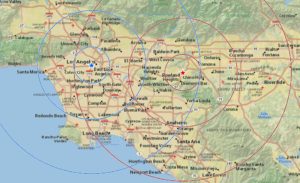

Grand Crossing is the competing stadium proposal. Located in the City of Industry, it sits at the intersection of the 57 and the 60 freeways. The plan put forth by Majestic Realty Co. is located almost exactly in the geographic center of Southern California. Two and a half miles from San Bernardino County, five miles from Orange County, 12 miles from Riverside County, and situated in the eastern part of Los Angeles County, the stadium is within an hour drive for over 15 million people.

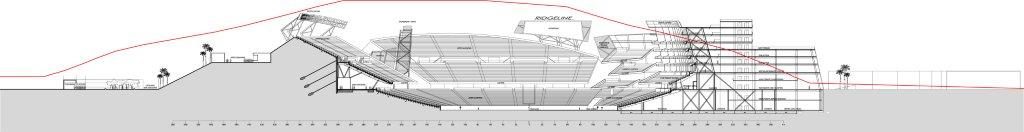

Sprawling across 600 acres, the stadium would be sunk into a hillside with a projected capacity of 75,000 fans. The overall plan includes 25,000 parking spaces, beach volleyball courts, clubs, and retail developments to make it a destination spot for tailgaters. “We are trying to create an experience that you can’t have by watching it on television,” says John Semcken, Vice President of Majestic Realty Co.

If anyone knows how to get sports arenas built in Los Angeles, it’s Semcken. The naval academy graduate was instrumental in building Staples Center, and firmly believes that Grand Crossing is the right answer for Los Angeles. With ample parking, easy access from all directions and a Metrolink stop on the site, Grand Crossing’s strength is its proximity to the people. In contrast to Farmers Field, which is located in the heart of downtown LA, Semcken points out that “by moving the building inland a little bit, you’re now the same distance from Newport Beach as you are from Beverly Hills.”

The plan would be financed with one hundred percent private dollars, even with an $800 million dollar price tag. This is largely possible due to backing from Ed Roski, the billionaire tycoon who serves as the president, CEO, and chairman of the board for Majestic. Roski has agreed to give the land for the stadium to any team in exchange for the right to purchase a quarter of the team at the market price.

The overall economic impact of the stadium is projected to create 18,000 jobs and $762 million in annual revenue for the region. Majestic proudly insists Grand Crossing will be one of the ‘greenest’ stadiums ever built. Its sunk-in design decreases the amount of steel necessary for construction, and its concourses are outside, capitalizing on the spacious property as well as Southern California’s warm weather. The developer’s economic impact study estimates over $21 million in tax revenue for local governments in the region, although the study did not break the impact down by county. Majestic’s bid also received special support from the State of California. In 2009, Governor Schwarzenegger signed a bill exempting the stadium from many provisions of the California Environmental Quality Act in an effort to eliminate some of the ‘red tape’ of government regulation.

Semcken believes that the stadium’s impact will be not only economic, but also psychological. By building the stadium farther inland, he believes that the ‘center’ of Southern California will also move east. “Football is the catalyst,” says Semcken, but the real benefit, he insists, is in the increased awareness and appreciation for the Inland Empire that will come as a result of this project. “Everywhere, people underestimate the economic strength of the Inland Empire, both San Bernardino and Riverside counties.” Majestic and its team have already acquired all the necessary permits and licensing, and construction could begin tomorrow if a team agreed to relocate. Roski believes the new stadium could be ready for the 2014 season if that happens.

Both plans are optimistic. Many in Los Angeles and the rest of the country are skeptical that either plan will succeed, at least in the near future. First, the obvious problem is that no team has committed to relocate. The NFL has said that it does not want to expand, which means that one or two teams would have to pack up and move to Southern California. According to CBS Los Angeles, the five teams considering a move are the Minnesota Vikings, San Diego Chargers, Oakland Raiders, St. Louis Rams and Jacksonville Jaguars. For a time, some even thought that the 49ers may be considering travelling south. But progress on the plans for a new stadium in Santa Clara make that possibility very unlikely.

Other factors also stack up against professional football in Los Angeles. The NFL imposes huge relocation fees on teams that decide to move. Also, the LA Times reports that the NFL just signed new television contracts with FOX, NBC, and CBS in December, 2011, which lock in high revenues for 10 years. This significantly reduces the NFL’s incentives to try to raise revenue by expanding to the LA market.

Less quantifiable, but just as relevant are cultural concerns. Some argue that Los Angeles and the NFL just are not a good fit. Whatever the reason, whether it is the past departures of the Raiders or Rams, loyalty to successful college football programs at USC and UCLA, or simply LA’s habit of living without professional football, some say Angelenos are not dying for a team. And they cite statistics. Currently, only 67,643 people had supported Farmers Field online petition out of the 15+ million people living in the Los Angeles area.

Los Angeles has been without professional football since 1995. Since then there have been many efforts to bring teams back to the City of Angels, but none have succeeded. Grand Crossing and Farmers Field have proceeded farther than any previous attempts. Both claim they can begin construction immediately. The result of each proposal’s dealings with the NFL, various teams, local governments, and the state will have a large impact of the future of the Inland Empire and the greater Southern California basin.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.