Placed on the Ballot by Petition Signatures

Research Assistant: William Frankel ’21

Purpose

Proposition 3 would authorize $8.9 billion in general obligation bonds for water infrastructure and environmental projects.

Background

Californians get water from three main sources. First, the majority of the water Californians use comes from rain and melted snow, which flows into streams and rivers. The areas where these streams and rivers begin are known as “watersheds.” Dams, reservoirs, and canals help deliver this water around the state. Second, water is pumped from underground, especially during years with less rain and snow. It is known as groundwater. Finally, a small share of California’s water comes from “water recycling,” through which wastewater in sewers is cleaned and reused.[1]

Spending on water-related projects is done by both California’s state and local governments. Local agencies, including water districts, cities, and counties, spend most of the money that goes towards providing water for drinking and farming or protecting from floods. That spending amounts to $25 billion annually. It is mostly financed by Californians’ water and sewer bills, with a substantial minority from grants and loans to local governments from the state.[2]

In recent years the state also directly spends about $4 billion annually to support water and environmental protection projects. It mainly uses general obligation bonds to pay for these projects.[3]

General obligation bonds are repaid using the state’s general fund, the account of money that the state appropriates for most of its services. General obligation bonds have to be approved by voters before they are issued. These bonds are sold to investors, who give money to the state up-front (to fund the project) in exchange for repayment from the state, with interest, later. These repayments are made annually until the bonds are paid off. Paying for projects with bonds is ultimately more expensive than paying up front because the state most pay both the cost of the bonds, “principal payments,” and the cost of interest, “interest payments.” [4]

As of July 2018, the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) reports that California currently has $83 billion of general obligation bonds on which it is making annual payments. Californians have also approved $39 billion of general obligation bonds that have not yet been sold. The state is currently paying $6 billion annually from the general fund to repay bonds.

Californians most recently voted on a water bond measure four years ago. A 2014 ballot proposition authorized $7.12 billion in bonds for water infrastructure and watershed protection.[5] As of the 2017-18 fiscal year, the legislature has appropriated more than 86 percent of those funds. The biggest projects funded by those bonds, in order as measured by spending, have been: water storage; protecting water sources; groundwater sustainability; drought preparedness; water recycling; safe drinking water; and flood management.[6]

Proposal[7]

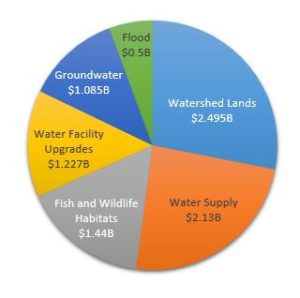

Proposition 3 would authorize $8.9 billion in new state general obligation bonds for water-related projects. Those funds would be divided into the following six categories as follows:

- $2.1 billion for water supply, including money for collecting and cleaning up rainwater, cleaning up drinking water, recycling wastewater, and activities that decrease how much water people use, like paying some of the costs for people to install low-flow toilets or replace lawns with plants that use less water.

- $1.4 billion for fish and wildlife habitats, for projects that could include increasing the amount of water that flows to a wetland or river or buying undeveloped land to keep it in a natural state.

- $1.2 billion for water facility upgrades, including money for repairing federally owned canals, building canals that connect local reservoirs and communities, repairing state-owned dams, and planning changes for aqueducts.

- $1.1 billion for groundwater, including money for clean groundwater, and helping water to soak back into the ground for future use, known as “groundwater recharge.”

- $500 million for flood protection, including money for expanding floodplains and repairing reservoirs, which would, in turn, also improve fish and wildlife habitat, increase water supplies, and improve recreation opportunities.

In contrast to most water and environmental bonds, the Legislature would not appropriate the funds in the annual state budget. Instead, the proposition continuously appropriates the bond funds to more than a dozen different state departments when they are ready to spend them. Departments would spend some of the funds to carry out projects themselves. But most of the funds would be awarded as grants to local government agencies, Indian tribes, nonprofit organizations, and private water companies. For some funding related to protecting the water supply, grant recipients would have to provide at least $1 in non-state funds for each $1 of grant funding they receive.

The proposition has several requirements to help communities with lower average incomes. For a few spending subcategories, the proposition requires that funding is spent on projects that benefit these communities. Also, in many cases, disadvantaged communities that receive grants would be exempt from matching fund requirements described above.

Separate from the $8.9-billion bond, Proposition 3 also changes how the state spends some existing funding related to Greenhouse Gasses (GHGs). California currently has a “cap-and-trade” program, which requires some companies and government agencies to buy permits from the state to release GHGs. The program increases electricity costs for water delivery systems, such as pumps and water treatment plants. Proposition 3 requires that a portion of the funding the state receives from the sale of GHG permits be provided to four water agencies: the California Department of Water Resources; the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California; the Contra Costa Water District; and the San Luis and Delta Mendota Water Authority. The amount of funding they receive would be equal to each agency’s additional electricity costs associated with cap-and-trade. The LAO estimates these costs to be tens of millions of dollars annually. The agencies, in turn, would be required to spend the funds from the rebate on water conservation programs.

Fiscal Impact[8]

While the cost to pay off the principal payments would be equal to the size of the bond – $8.9 billion – the total cost to the state would depend on the interest rates in effect at the time they are sold, the timing of bond sales, and the time period over which they are repaid. The LAO estimates that interest costs over the life of the bonds will add $8.4 billion over the next 40 years to the $8.9 billion principal, resulting in a total of $17.3 billion. This would add an average annual cost of $430 million to the state budget, or roughly .03 percent of the current general fund budget.

Proposition 3 would have a mixed effect on local governments’ fiscal outlook. In cases where state funds replace money that local governments would have spent on projects anyway, Proposition 3 would reduce local spending. But in other cases, Proposition 3 could increase local spending, as local governments build more or bigger projects than they would if state funds were not available, which often require local matching funds. Ultimately, the LAO estimates that on balance, the measure would result in savings to local governments, averaging around a couple hundred million dollars annually for the next few decades.

Supporters

Proposition 3 is supported by U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, U.S. Reps. Jim Costa (D-CA), John Garamendi (D-CA), and David Valadao (R-CA), and GOP gubernatorial candidate John Cox. The Yes on 3 campaign is comprised of a coalition of conservation groups, agricultural organizations, environmental and social justice organizations, local governments and water agencies, labor organizations, and businesses, including the California Chamber of Commerce.[9]

Four committees have been formed to support the ballot measure. Listed alongside their total expenditures as of June 30, they are:

- Agricultural and Dairy Community for Safe Drinking Water and a Reliable Water Supply: $1,330

- Californians for Safe Drinking Water a Clean and Reliable Water Supply in Support for Proposition 3: $869,482

- California Waterfowl Association for Safe Drinking Water and a Clean and Reliable Water Supply: $75,739

- American Pistachio Growers: $100,000

- Northern California Water Association for a Water Bond: $5,814[10]

Arguments of Supporters[11]

Supporters say Prop 3 would:

- Prepare California for the inevitable next drought and flood

- Help disadvantaged communities and guarantee a basic human right to water

- Improve the water quality of Californian rivers, lakes, bays, and oceans

- Protect local food supply and locally grown farm products

Opponents

Notably, the Sierra Club of California is opposed to Proposition 3.[12] No committees are registered to oppose Proposition 3.[13]

Arguments of Opponents[14]

Opponents say Prop 3 would:

- Fund wasteful projects to attract rich investors who will profit at the taxpayers’ expense

- Bypass legislative oversight of the spending or programs it would create

- Let the parties responsible for environmental degradation off the hook by cleaning up the environment with taxpayer money

- Take general fund money away from other spending priorities

Conclusion

Voting Yes on Prop 3 would authorize $8.9 billion in general obligation bonds for water infrastructure and environmental projects.

Voting No on Prop 5 would not authorize $8.9 billion in general obligation bonds for water infrastructure and environmental projects.

For more information on Proposition 3, visit:

Download PDF

[1] https://lao.ca.gov/ballot/2018/prop3-110618.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] https://lao.ca.gov/ballot/2018/overview-state-bond-debt-110618.pdf

[5].https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_3,_Water_Infrastructure_and_Watershed_Conservation_Bond_Initiative_(2018)

[6] http://www.ppic.org/blog/californias-water-bond-spent/

[7] https://lao.ca.gov/ballot/2018/prop3-110618.pdf

[8] Ibid.

[9] https://waterbond.org/official-endorsement-list-for-the-water-supply-and-water-quality-act-of-2018/

[10] http://cal-access.sos.ca.gov/Campaign/Measures/Detail.aspx?id=1399109&session=2017

[11] https://waterbond.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Argument-and-Rebuttal-Proposition-3-1.pdf

[12] https://www.sierraclub.org/sites/www.sierraclub.org/files/sce/sierra-club-california/PDFs/FactSheet_Proposition3_Opposition-July18.pdf

[13] http://cal-access.sos.ca.gov/Campaign/Measures/Detail.aspx?id=1399109&session=2017

[14] http://www.sierraclub.org/sites/www.sierraclub.org/files/sce/sierra-club-california/PDFs/FactSheet_Proposition3_Opposition-July18.pdf