By Sam Stone ’14

Rep. David Drier (R-San Dimas), Chairman of the House Rules Committee cruised to a double-digit victory in California’s 26th Congressional District last November, trouncing his opponents with relative ease. Rep. Jerry Lewis, (R-Redlands) crushed his challenger by nearly 30 points last fall. Yet, come November 2012, both Congressmen may very well be out of a job. How could two popular and powerful Congressmen with more than 70 years of Congressional experience between them be in such political danger? It’s not a shocking scandal, a shortage of campaign cash, or any drastic ideological shift. The answer is redistricting, an esoteric yet tremendously important political procedure that shakes each and every level of the American political system every ten years. And this time around, the Inland Empire sits squarely at the epicenter of a political earthquake.

Background

Strictly speaking, redistricting is the constitutionally mandated procedure in which district boundaries are redrawn to accommodate changes in population. The United States Constitution requires that Americans are represented equally, and thus it is necessary to redraw political boundaries to balance population numbers in political districts. The redrawing of Congressional lines occurs every 10 years, following the tabulation of the U.S. Census and the process of reapportionment (the reallocation of representatives among states based on population shifts).

For California, 2011 redistricting marks a number of firsts. For the first time since California earned its statehood in 1850 (except 1920, in which reapportionment did not occur), the Golden State will not see an increase in its Congressional delegation following the Census. While states like Texas, Colorado, and Georgia will each gain a few more seats in the House of Representatives, a slowing of population growth in California means that the status quo of 53 representatives will remain in place for the next ten years. Perhaps even more historic, 2011 marks the first redistricting cycle in which the power of redistricting has been granted to a brand new, voter-approved organization: the California Citizens Redistricting Commission (CRC).

The California Citizens Redistricting Commission

The California Citizens Redistricting Commission, created with the passage of Proposition 11 in 2008, was initially given the task of handling redistricting exclusively for state legislative districts (and the Board of Equalization). However, its role expanded to include congressional redistricting with the passage of Proposition 20 in 2010. Both propositions had to overcome significant opposition to their passage. The commission, comprised of five Democrats, five Republicans, and four commissioners unaffiliated with either major party, was supported heavily by Governor Schwarzenegger and state Republicans. They believed maps produced by a bipartisan redistricting process would be more favorable to the GOP than ones authored by the legislature, with its majority of Democrats in both chambers. Conversely, Democrats and many incumbents feared the fallout of a group of citizens by drawing lines from scratch. Following the narrow passage of Proposition 11 and the easy approval of Proposition 20, the battle shifted to the CRC.

The process of picking commission members began in December 2009. Through a complex selection process meant to eliminate candidates with any direct ties to state politicians or parties, the state auditor’s office narrowed the applicants from more than 25,000 to 60 candidates. By November of 2010, the first 8 commissioners (randomly selected from the final pool) had been chosen. These 8 commissioners selected 6 more, finalizing the 14 member commission by the end of the year. In 2011, the commission began its work in earnest. Over the course of the next 8 months, it would crisscross California, take public input from thousands of people, hire numerous staffers (to some controversy), and gradually formulate operational procedure for the first itineration of the most powerful redistricting commission in the nation.

The first signs of forthcoming political upheaval became clear when the CRC announced it would prioritize geographic and cultural factors such as compactness, and city, county, and community boundaries over political considerations in designing the maps. Existing districts and the locations of incumbents’ homes would not play a role in the CRC’s work. The commissioners would instead start from scratch in drawing 53 districts for Congress, 80 for the State Assembly, 40 for the State Senate, and four for the Board of Equalization.

It took little time for the CRC to run into controversy, however, as Republicans criticized the commission for hiring legal and technical consultants with perceived Democratic Party ties. (The Rose Institute submitted an unsuccessful bid for the technical consulting services). Nevertheless, the CRC marched onward with public comment and released the first of two planned draft maps on June 10. The map was met with mixed reviews. Supporters praised improved compactness and a noticeable reduction in community splits while expressing concern over an overall lack of competitive seats. State Republicans attacked the commission for crafting a map that would likely produce several Democratic gains in Congress and the State Senate. Latino advocacy groups such as the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) voiced outrage that the CRC draft map created few Latino majority seats.

Additional concerns emerged as it became increasingly clear that with just a few weeks left before their August deadline, the CRC continued to consider wholesale changes to the first draft maps. In a controversial vote on July 12, the commission moved to skip the creation of a second full draft map in order to proceed straight to a final map. While CRC opponents such as the California Friends of the African American Caucus criticized the move as an affront to transparency, describing the vote as just the “latest shenanigans” of the CRC, commissioners defended their decision. Commissioner Jeanne Raya claimed the vote would give the CRC “more time to deliberate thoughtfully” and “more opportunity for the public to interact with us in live drawing sessions.”

On August 15, the CRC formally approved finalized legislative redistricting plans in a 13-1 vote and the Congressional plan 12-2. While most commissioners who voted in favor of the plan spoke highly of the plan, the sole dissenter on the legislative plans, Commissioner Michael Ward, alleged that “the commission broke the law,” and “simply traded the partisan, backroom gerrymandering by the Legislature for partisan, backroom gerrymandering by average citizens.” In an LA Times Op-Ed, Commissioner Cynthia Dai responded to CRC detractors, declaring that the CRC’s “commitment to a fair process trumped partisan allegiances,” and boasting that “we were able to eliminate partisan gerrymandering and draw 177 districts for the state Assembly and Senate, Board of Equalization and Congress on time and under budget.”

Redistricting Analysis

A district-by-district analysis of the California Redistricting Commission’s maps illustrates the far reaching nature of the CRC’s work. The new maps drastically reshape congressional and state legislative representation in the Inland Empire. As a result of efforts by the commission to create reasonably compact districts and preserve communities of interest, the new maps offer districts that are, for the most part, much more compact than their predecessors.

By ignoring existing districts and focusing on compactness and communities, the CRC has produced a Congressional map that will result in significant political turnover in the Inland Empire. Longstanding Republican incumbents David Dreier (San Dimas) and Jerry Lewis (Redlands) no longer reside in safe Republican districts. The options available to two of California’s most notable Congressmen are few: retire, move, or wage tough battles to hold onto their seats. In addition, a handful of open seats have emerged in the area, offering up-and-coming politicians a rare opportunity to run for Congress without facing competition from powerful incumbents. All in all, it appears the commission’s work has created three competitive seats and two or three open seats in the Inland Empire’s Congressional delegation. For a regional delegation that has seen little to no turnover in the past twenty years, this is nothing short of a political earthquake.

San Bernardino County Congressional Districts

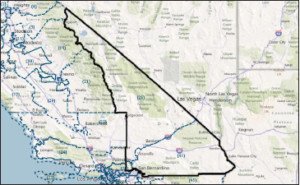

The 8th District, geographically massive, is primarily a combination of the rural 31st and 25th Districts. It stretches from Bridgeport (near Yosemite) hundreds of miles south to Yucca Valley, and encompasses the cities of Victorville, Ridgecrest, Barstow, Baker, Mammoth Lakes, Death Valley, Highland, East Highland, and Yucaipa.

A hotbed of the California Tea Party, the 8th leans heavily Republican, but neither incumbent Jerry Lewis (R-Redlands) nor Buck McKeon (R-Santa Clarita) reside in the new district. While Rep. McKeon will almost certainly run in the 25th (a safe Republican seat much closer to home), Rep. Lewis is in a bit of a jam. He could run in the 31st District (where he now lives), but he would likely face a very competitive race in somewhat unfamiliar Democratic-leaning territory. Legally, he can still run in the 8th even though he does not actually live in the district, but even this could be a danger given the area’s history of voting out incumbents. If Rep. Lewis does retire, San Bernardino County Supervisor Brad Mitzelfelt (R) has promised to enter the race, and would be a heavy favorite. In any case, this is an open seat, but almost certain to remain in Republican hands given the GOP’s ten point edge in registered voters.

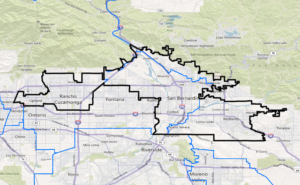

The new 31st District attempts to unify the city of San Bernardino, previously split between the 41st (Rep. Jerry Lewis, R-Redlands) and 43rd (Rep. Joe Baca, D-Rialto) Districts. It includes San Bernardino, Rancho Cucamonga, Upland, Colton, Verdemont, Muscoy, Grand Terrace, Loma Linda, Redlands, Crown Jewel, Meritone, and West Highlands.

Democrats hold a small registration advantage over Republicans in this district (41 percent to 37.5 percent), which does not bode well for Rep. Jerry Lewis, should he decide to run in his new home district. Rep. Joe Baca could run here as well, in which case he would be a slight favorite, but he may instead opt to run in the 35th District, where he would be a strong favorite against any Republican. Rep. Baca and Rep. Lewis each appear to be waiting to see if the other will move to another district, despite pressure from Democratic and Republican party officials to stay and win in what is seen as a winnable race for either incumbent. If both incumbents run in this district, the 31st could be one of the marquee races of 2012.

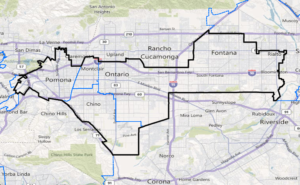

The 35th District includes much of the remainder of San Bernardino County: Fontana, Ontario, Montclair, Chino, Montclair, Rialto, and Bloomington. This area was previously split into four separate districts. The 35th also includes Pomona from Los Angeles County.

This seat will likely be a safe Democratic seat, given the sizable registration advantage the Democrats hold (48.6 percent to 29 percent), and the large number of Latinos in the area. President Obama won more than 66 percent of the vote here in 2008, making it an appetizing prospect for district resident Joe Baca (D-Rialto) to run here rather than risking an expensive contest with Rep. Jerry Lewis in the 31st. Somewhat complicating things for Rep. Baca, however, State Senator Gloria Negrete McLeod (D-Chino) has all but claimed this district as her own. The 35th District closely resembles Senator McLeod’s current district, giving the Senator somewhat of an incumbency advantage. Senator McLeod and Rep. Baca are no strangers to conflict either. In 2006 Congressman Baca’s son, Joe Baca Jr., was beaten in the Democratic State Senate primary by Senator McLeod. Further complicating the picture, Democratic Assemblywoman and former Pomona mayor Norma Torres has also declared for the 35th district. With the “top two” primary system set to kick in next fall and a vast swath of Democratic voters in the district, it could come down to two popular Democrats battling it out in the general.

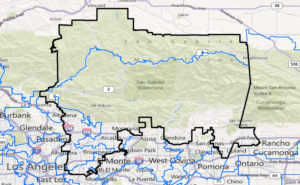

The 27th District is comprised of most of Pasadena and odd pieces of the north San Gabriel Valley. It includes Glendora, San Gabriel, Rosemead, Altadena, Arcadia, Temple City, Alhambra, and South San Gabriel. Once prominent members of Inland Empire districts, Claremont and parts of Upland have now been demoted to mere appendages of this Pasadena-dominated district.

Rep. Judy Chu (D-Monterey Park) has announced she will be running in the 27th District, and would be a heavy favorite to win, given the double digit Democratic edge (42 percent to 30 percent).

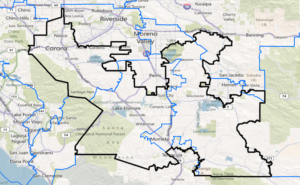

Riverside County Congressional Districts

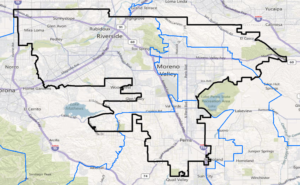

The 41st District includes the cities of Riverside, Moreno Valley, Glen Avon, Mira Loma, Rubidoux, Pedley, Sunnyslope, and Perris.

A major change is in store for residents of Riverside and the Moreno Valley area. Once split between Rep. Mary Bono Mack’s (R-Palm Springs) 45th District, Rep. Darrell Issa’s (R-Vista) 49th District, Rep. Ken Calvert’s (R-Corona) 44th District, and Jerry Lewis’s (R-Redlands) 41st District, the Riverside/Moreno Valley population now has a district of its own. The 41st offers Democrats an open seat with a moderate registration advantage (42 percent to 36 percent). Nevertheless, popular Republican Riverside County Supervisor John Tavaglione is favored for this seat over the only declared Democratic candidate, Mark Takano. There still remains a significant chance that other Democrats may jump into the race, and in all likelihood the 41st will be another close race to watch next election night.

The 36th District remains remarkably similar to its predecessor, the 45th District, trading Moreno Valley and Murrieta for San Jacinto, Banning, and Desert Hot Springs. Palm Springs, Cathedral City, La Quinta, Coachella, Indio, Hemet, Blythe, and the Riverside County portion of Joshua Tree remain in the district.

Mary Bono Mack (R-Palm Springs) remains a favorite, as the narrow partisan advantage she has traditionally held in her district remains effectively unchanged (42 percent to 39 percent). Rep Mack stands as one of the few Republican beneficiaries of the redistricting process, as her district remains largely intact and efforts to add Democratic-leaning Imperial County to the district were rejected by the Commission. Although the Democrats will likely again make a serious attempt to unseat Rep. Mack, the redistricting process does not appear to have affected Rep. Mack’s chances in the race.

The 42nd District also remains somewhat similar to its predecessor, the 44th District. The core of the district, including Corona and Norco is unchanged, but the district now moves south and east to include much of what used to be in Darrell Issa’s (R-Vista) 49th District. Key cities include Corona, Norco, Murrieta, Sun City, Canyon Lake, Wildomar, Lake Elsinore, Lakeview, and Nuevo. The Orange County portion of the old 44th is no longer included in the new 42nd, which is located entirely in Riverside County.

Much like the 36th District, the 42nd District is unlikely to undergo any significant political turnover. Rep. Ken Calvert (R-Corona) resides in the district, and Republicans enjoy a ten point registration advantage. Rep. Calvert, probably the biggest winner in this redistricting effort after facing significant reelection challenges in 2008 and 2010, will likely have a much safer seat than in years past.

What’s Next?

With the CRC’s plan formally adopted on August 15, California is now moving toward using the new lines for the 2012 election. To the dismay of Commission supporters, however, there remains a distinct possibility that the Commission’s work could yet unravel. The biggest danger to the CRC’s congressional plan is a Republican referendum. Several state Republican officials have expressed concern that the new maps will unfairly benefit the Democrats, who are poised to make several gains thanks to the new maps. If the Republicans are able to gather at least 505,000 signatures on a congressional referendum by November, then the CRC’s congressional plan will be suspended for 2012 and replaced with a court-drawn plan. Should the referendum pass and reject the CRC lines, the court-drawn plan will remain in place for the rest of the decade. Should the referendum fail, the court plan would only be used in 2012 and the CRC map will be used from 2014-2020.

Will such a referendum make it to the ballot? The answer is currently unclear. According to redistricting expert and Rose Institute fellow Douglas Johnson, getting the 505,000 signatures it takes to reach the ballot “is a matter of money.” If Reps. Dreier and Lewis decide to run for reelection, and dislike their election chances, they could throw their considerable financial strength behind the referendum. “[Dreier and Lewis] have the ability to essentially fund the referendum on their own,” says Johnson. Reps. Ed Royce, Gary Miller, and other GOP Congressmen displeased with the new lines could support the referendum as well.

So if the courts do end up drawing lines, what would they look like? Insiders speculate that the courts could produce districts similar to those drafted in 1991, the last time the courts drew the lines. The 1991 lines were “community oriented, with limited splits of cities and counties, and very competitive districts,” says Johnson. But where court-drawn lines will actually end up is anyone’s guess. While much of the rest of the state might closely resemble the 1991 plan, in the Inland Empire, Johnson says “there’s been so much growth in this area that anything that actually resembles the 1991 lines is not a possibility.” Whether the public pushes for a plan from the courts, or sticks with the California Citizens Redistricting Commission, one thing is certain: California’s congressional delegation will likely be facing a major shakeup come 2012.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.