Written by Luke Davis ’14

Conveniently located in close proximity to Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside, and Los Angeles counties, Ontario International Airport (ONT) provides a fantastic convenience to fliers in the Southern California area: the airport is small and easy to navigate, lines are short or non-existent, and in general, the flights run on time. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Ontario Airport experienced increasing passenger volume and airline support. Currently, though, the airport’s future is in jeopardy as its particular operational structure has rendered its costs much higher than comparable airports.

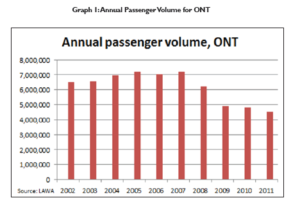

Ontario International Airport is owned by Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA), a department of Los Angeles city government, which also owns and operates Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and Van Nuys Airport. While Ontario Airport has done well in the past, its performance in recent years has concerned airport officials. Since 2005, Ontario Airport’s annual passenger volume has fallen 36 percent to just four and a half million. Airlines like JetBlue have abandoned the airport while domestic flights continue to be cut. Indeed, Ontario Airport’s continuing stagnation remains in contrast to LAX, which has emerged from the recession on a path toward progress.

Ontario International Airport is owned by Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA), a department of Los Angeles city government, which also owns and operates Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and Van Nuys Airport. While Ontario Airport has done well in the past, its performance in recent years has concerned airport officials. Since 2005, Ontario Airport’s annual passenger volume has fallen 36 percent to just four and a half million. Airlines like JetBlue have abandoned the airport while domestic flights continue to be cut. Indeed, Ontario Airport’s continuing stagnation remains in contrast to LAX, which has emerged from the recession on a path toward progress.

One notable problem with the airport’s operation is overstaffing. Although Ontario Airport currently budgets for 250 employees—down from over 300 in 2011—according to Ontario City Manager Chris Hughes this number still represents unreasonable overstaffing. He says that the airport should be employing around 100 fewer workers. Even if further cuts are to be made, Hughes also notes Ontario’s problem of staff inefficiencies and cutting necessary employees while retaining redundant positions, citing the lack of airport employees at terminals and the resulting clog of illegally parked vehicles as an example of the effects of wrongful staff reductions.

The most revealing indicator of Ontario Airport’s recent decline can be found in its high Cost per Enplaned Passenger (CPE), an industry metric used to assess the differences in costs between airports. Hughes estimates that Ontario Airport’s CPE for 2011 was somewhere between $13.50 and $14.00, considerably higher than the United States median of $6.75. The 2011 CPE is lower than Ontario’s 2010 CPE of $14.50, but still higher than that of LAX, $11, even though LAX is a much larger and more complicated airport to manage.

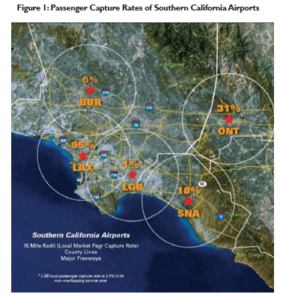

Regions in the United States are often served by multiple airports. Primary ones, like LAX, handle most of the traffic of a region while the secondary airports provide an alternative, whether to manage traffic, for geographic convenience, or for other demographic or economic reasons. As Figure 1 shows, Ontario Airport and its recorded fifteen-mile sphere of influence captures 31% of its local market’s passengers, in contrast to John Wayne Airport (SNA), which only captures only 18% of its local market. The difference is that John Wayne Airport has seen its passenger numbers rise: As the OC Metro reports, passenger volume in July at John Wayne Airport increased by four percent in 2012, in comparison to July traffic of 2011. This contrast highlights the missed potential of Ontario Airport: How can an airport such as Ontario, which captures a higher rate of passengers in an area already gifted with enormous economic potential, face such problems, while a neighboring airport, whose biggest problem is handling its successful expansion, attracts even less of its local market than Ontario? According to Hughes, Ontario Airport should not be even using the fifteen-mile radius figure, asserting that it makes more sense to use a 20- or 25-mile radius, given geographic economy of the region. Hughes also states that with the exception of Ontario Airport, no other secondary airport in the United States is more expensive than the primary regional airport. And this higher cost for both airlines and passengers is at the heart of Ontario Airport’s problems — airlines continue to take their business elsewhere because it is cheaper to do so. Put simply, as the most expensive airport in Southern California, Ontario Airport is just not competitive.

Which is not to say that the demand for regional airport travel is minor: according to Cynthia Kurtz, president and CEO of the San Gabriel Valley Economic Partnership, Ontario Airport remains hugely important to the eastern San Gabriel Valley. Asserting that Ontario Airport has “always identified with the Inland Empire,” Kurtz cites a survey of businesses in the San Gabriel Valley which resulted in local business owners emphasizing ease of regional airport travel as a top priority for business support. And as the San Gabriel Valley is located between two airports (Bob Hope Airport in Burbank on the west, Ontario Airport on the east), regional businesses depend on their transportation services for both freight and executive travel. Tom Freeman, Commissioner of the Office of Foreign Trade of Riverside County, feels similarly about Ontario Airport’s importance to his region, calling the airport “absolutely critical” for business attraction, activity, and retention in Riverside County. Also citing the county’s “robust, multi-billion dollar” tourism industry as key to the regional economy, Freeman asserts that Ontario Airport needs to provide sufficient carriers and flights to attract tourists from major hubs. Freeman sees Ontario Airport as a playing a key role in supporting growing industries like logistics on an international scale. Because the airport has been losing flights under current leadership, Freeman identifies a need to reach out to and work with the aviation community, and, if necessary, subsidize flights to mitigate the airport’s high costs.

To offset these increasingly high costs, Ontario Airport has employed some temporary measures to avoid complete disaster. It has used both parking revenue and reserve funds to equalize operational costs. As Hughes explains, this dip into other funds represents an artificial mechanism to deflate costs and will likely secure only two years of operational sustainability. In addition, Ontario Airport has dabbled in offering incentives to airlines to operate at the airport, proposing waiving certain terminal rents and promising increased efforts in marketing. However, airlines remain reluctant—Hughes explains that airport incentives do little to affect sustained increased traffic.

To offset these increasingly high costs, Ontario Airport has employed some temporary measures to avoid complete disaster. It has used both parking revenue and reserve funds to equalize operational costs. As Hughes explains, this dip into other funds represents an artificial mechanism to deflate costs and will likely secure only two years of operational sustainability. In addition, Ontario Airport has dabbled in offering incentives to airlines to operate at the airport, proposing waiving certain terminal rents and promising increased efforts in marketing. However, airlines remain reluctant—Hughes explains that airport incentives do little to affect sustained increased traffic.

As for marketing, the issue remains complicated. On one hand, an overhaul and re-budgeting of the airport’s marketing initiatives is essential, as it would serve to expand the airport’s sphere of influence and thus pitch to potential leisure and business travelers, the latter category being underrepresented. According to Hughes, despite the fact that over 8,000 businesses in Ontario use the airport, the airport fails to recognize these travelers as a primary demographic worth monetizing. And the marketing budget has been slashed significantly over the years: at its peak in the early 2000s, it totaled to over $1 million. Now, it is around $200,000. On the other hand, a marketing budget alone cannot fix the airport’s problems, so some airlines worry that these increased marketing costs will simply make the airport more expensive at a time when airlines are not even sure if they will stay at Ontario Airport.

The common theme throughout the assessment of the airport’s problems is that of staying power: How can the airport bring down costs to not only attract airlines but make them stay? Hughes proposes a few potential paths, but he emphasizes that any solution will involve a “multipronged” approach. One idea of long-term cost reduction involves privatizing the airport. According to Hughes, while this may be an efficient option, the length of time that this process would take, with Federal Aviation Administration regulations and airlines disagreeing over lease agreements, makes the idea less appealing.

Rather, Hughes sees Ontario Airport’s most promising path as one involving a regional joint powers authority, between the City of the Ontario and San Bernardino County, to receive the airport in a transfer from LAWA. While Los Angeles, as Hughes asserts, could still be involved in Ontario Airport’s future, the airport is a regional airport and should thus be supported by a regional authority. Hughes sees the current time as ripe: While LAWA has deflected criticism of its operations management at Ontario Airport by citing the effects of the late-2000s recession, the airport’s current total passenger volume has dropped to 1983 levels while the region has added two million people and over 600,000 jobs since then. To Hughes, this growth provides the proof that there is indeed a market for Ontario Airport to exploit should its costs decrease.

So while Ontario Airport’s future remains uncertain, the picture is not all bleak. As Hughes believes, the newly-formed Ontario International Airport Authority’s work on setting up a sub-committee to aid in economic development surrounding the airport is important. The Ontario International Airport Authority was formed through a Joint Powers Agreement between the City of Ontario and the County of San Bernardino. The Ontario City Council first appointed two of its own members, Alan Wapner and Jim Bowman, to the authority, later approving San Bernardino County Supervisor Gary Ovitt; Lucy Dunn, president and CEO of the Orange County Business Council; and Ronald O. Loveridge, Mayor of Riverside. The authority, according to the San Bernardino Sun, was established with the intent of creating a viable business plan for Ontario Airport, writing bylaws, and following the communication between airport management, local officials, and the City of Los Angeles on the subject of the airport’s potential transfer of control. Assuming the Authority drafts a multifaceted business plan, development at the airport could be utilized to its full potential. Hughes believes that the Authority’s changes could render, through ancillary revenues and contracting, the airport a zero-cost operation for airlines, a notion which recognizes a crucial fact: the airport needs to serve both passengers and airlines in order to lower costs and attract business.

On September 27, a subcommittee of the U.S. House Transportation and Infrastructure, the Subcommittee on Aviation, met to examine the economic impact and future management of Ontario International Airport. The subcommittee heard testimony from members of the Ontario International Airport Authority and Miguel Santana, Los Angeles City Administrative Officer. Testimony emphasized the importance of the regionalization of airports. Authority member Wapner pointed out the benefits to all regions and parties, including LAWA, if control of Ontario Airport is transferred, citing the economic usefulness of governing and organizing regionally. The focus of regional re-appropriation of airport control and its benefits was the main theme of the discourse, suggesting that the City of Los Angeles and other regional governments may crucially find some common ground to move forward in reform of Ontario Airport. While the process of reforming and transferring ownership of the airport will likely be a complex challenge, it has nonetheless begun and could point to a better, more connected Inland Empire. As Chris Hughes says: “We wouldn’t be so aggressive in the campaign to regain local control [of ONT] if we didn’t think it mattered.”

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.