by Sophia Helland ’20 | April 2018 Download PDF

ABSTRACT

The Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA) was passed by Congress in 2010 in an attempt to revitalize tribal justice systems for the first time since the 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA). Provisions in ICRA related to justice reforms were particularly ineffective in increasing tribal sovereignty and decreasing crime. Despite the good intentions of TLOA, however, there are currently two major flaws in the act. First, enforcement has been difficult due to a lack of funding and cultural sensitivity. Second, TLOA has exacerbated existing confusion over jurisdictional authority in states that have been delegated jurisdiction over tribal affairs. Critics claim that TLOA has actually created even more confusion. California, which has been delegated this authority, represents a useful case study of the impact TLOA has had on tribal justice systems due to a large number of federally recognized tribes within the state. This paper will examine the Act’s implementation and compile crime statistics on Native American reservations within California with independent justice systems using data provided by county sheriff ’s departments and analyze the implications of these data. Unfortunately, I do not find evidence of a trend in the crime data, but there is evidence that data is not uniformly reported. While it is difficult to isolate a single causal mechanism for increased or decreased crime rates from crime statistics alone, they are still useful research tools that have not previously been compiled into a comprehensive list.

INTRODUCTION

Since 1953, the United States government has taken deliberate aim at decreasing crime on Native American reservations through a variety of legislative and regulatory efforts. One of the most recent and significant pieces of legislation was passed in 2010: the Tribal Law and Order Act. The Act had far-reaching implications for criminal justice reforms on tribal lands, but little research has been done on the act, particularly pertaining to states that have criminal jurisdiction over law enforcement and crime prevention on reservations in place of the federal government. The aim of this paper is to examine how the Tribal Law and Order Act has been implemented in California and provide context for its successes and failures by gathering crime statistics for a select group of reservations to gauge whether there the Act has been successful at decreasing crime. The county sheriffs’ departments responsible for tribes with their own courts or police were contacted for statistics, as these tribes would be most affected by the Act. This paper will begin by explaining the legislative history of justice reforms on tribal lands in Section I, then discuss how California has implemented the Act and how tribes have responded to it in Section II. Section III outlines the data collection and methods used. Section IV presents the findings of this research.

SECTION I: CONTEXT AND LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

The Indian Civil Rights Act, The Tribal Law and Order Act, and PL-280

Since the Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA) was passed in 1968, federally recognized Native American tribes could sentence and convict criminals for crimes taking place on tribal lands, by Native American offenders.[1] While the Act was a step forward for recognizing tribal sovereignty and protecting Native Americans, it ultimately proved to be ineffective. Tribal courts were only given the right to sentence felons to six months in prison and $500 in fees (later extended to one year and $5,000) under the assumption that more serious crimes would be turned over to the federal government.[2] The federal government has generally not lived up to its promise, however, and most crimes taking place on reservations are either not prosecuted or result in a very short sentence from tribal authorities because a shorter sentence is considered better than no sentence. The Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA) was passed in 2010 to address these deficiencies.

The TLOA grants additional duties to the federal government and tribal authorities. The federal government now has a greater responsibility to collect crime data on tribal communities to track the progress of the Act and identify which programs are effective. They were also required to increase federal involvement in prosecuting crimes. Simultaneously, tribes were required to reform their justice systems to be more in line with the Constitutional due process. In return, tribes are given stronger sentencing authority. The Act also aimed to clarify jurisdictional problems between federal, state, and tribal governments. Usually, the federal government prosecutes serious crime on tribal lands. However, in 1953, six states took over the federal government’s duties and were granted criminal and some civil jurisdiction over reservations within their states. The so-called PL-280 states (based on the law’s origins in Public Law 83-280) include Alaska, California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wisconsin. According to the U.S. Census, these six states represented about 24% of the American Indian and Alaska Native population in the United States in 2016. The law also expanded criminal jurisdiction in “optional PL-280” states, granting Florida, Idaho, and Washington the option to assume partial or whole jurisdiction of reservations.

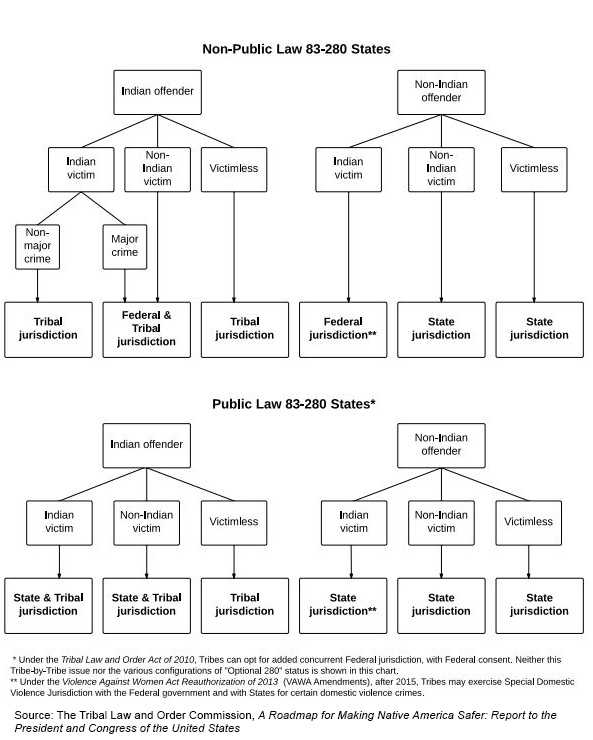

Research by the Tribal Law and Order Commission has shown that tribes tend to have less faith in states as the main prosecutor, because “states often have proven to be less cooperative and predictable than the Federal government in their exercise of authority.”[3] Distrust of the state government based on history has undermined enforcement in PL-280 states. The Tribal Law and Order Act thus allowed tribes to request that the federal government assume criminal jurisdiction again, but this sometimes created even more confusion over jurisdiction. At this point, however, very few tribes in PL-280 have gone through the process of requesting federal jurisdiction. Figure 1[4] explains who gains jurisdiction based on what groups are involved in a crime; it clearly a convoluted process with many opportunities for mistakes.

FIGURE 1. General Summary of Criminal Jurisdiction on Indian Lands

Tribal Sentencing Rights

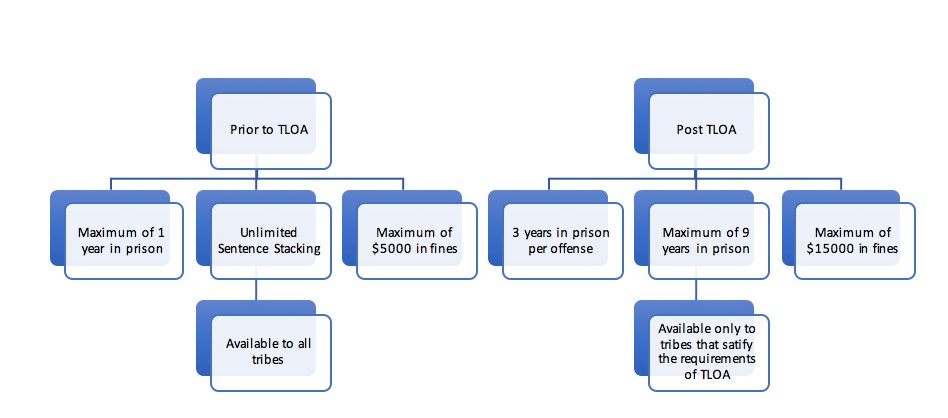

Prior to TLOA, tribes had limited sentencing authority and narrow jurisdiction, particularly in PL-280 states, as detailed in Figure 1. However, many tribes found a loophole in ICRA after the federal or state government largely failed at prosecuting crime on reservations. “Sentence stacking” was the practice of assigning time in prison or fines for each offense committed.[5] The Tenth Circuit upheld the practice in 2010 (and the Supreme Court declined to take the case on appeal) in Romero v. Goodrich but sentence stacking remains controversial. TLOA both codified and limited sentence stacking. The Act gave tribes the ability to sentence defendants to up to three years in prison per offense and nine years for any given court proceeding.[6] This got rid of unlimited sentence stacking but gave tribes stronger sentencing authority. Figure 2 outlines the changes to sentencing. However, TLOA also required tribes to reform their justice systems to be more compatible with criminal justice systems in the rest of the U.S. in return for these powers. Most tribes do not actually have the funds to do this or think that the requirements would override culturally significant facets of their justice systems and would be considered illegitimate by most members. Enforcing new standards takes away local control and culturally significant practices[7] Only two tribes instituted the Act in 2012[8] and seven tribes did by 2016 none of which were tribes in California, according to the Tribal Law and Order Resource Center. As a result, it is the richer tribes, with already lower crime rates, that gained stronger sentencing rights, while poorer tribes did not.[9]

FIGURE 2. Tribal Sentencing Authority Prior Before and After TLOA

SECTION 2: IMPLEMENTATION AND RESPONSE

Federal and State Programs for T.L.O.A.

Since 2010, many different programs have been created to uphold the provisions of TLOA. At the federal level, there have been major revisions such as the Violence Against Women Act, which was signed into law in 2013, and allowed for tribes to have increased sentencing and jurisdictional power in cases of domestic violence. While this only applies to one crime, domestic violence is a crucial issue and increased jurisdictional powers for all tribes is a necessary facet of combating violence. There have also been increased efforts to support the implementation of the Tribal and Territory Sex Offender Registry System, which allows for tribes to create a public website to track sex offenders. TLOA has also increased efforts at cooperation and communication among prosecutors, law enforcement officers, and tribal governments.[10] California has specifically held several Tribal Court-State Court Forums to discuss the best ways to implement TLOA among California tribes.

As of now, there have been few efforts at data collection at the federal level for PL-280 states. A few tribes have communicated their crime statistics to federal reporting agencies, such as the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report but, for unclear reasons, the tribes reporting are inconsistent from year to year and only a very limited number of tribes in PL-280 states report. The Bureau of Justice Statistics has been planning to release reports on law enforcement and tribal jails/justice systems, but the reports are unpublished as of this writing. California provides crime statistics by county, but tribal lands are grouped with the county they reside in, making it difficult to find reports about individual tribes.[11]

Tribal and State Response

While the Tribal Law and Order Act has generally been well received for its good intentions, there are several aspects of the Act that have been particularly unpopular among tribes. Provisions requiring tribes to change their justice systems were particularly problematic, especially for tribes in PL-280 states. As mentioned above, these reforms are generally expensive to implement. Grants have generally been badly publicized and difficult to obtain, and high costs can disadvantage tribes with limited resources. Throughout the country, scarce resources have been the biggest problem with the implementation of the Act, but the problem is particularly pronounced in PL-280 states.[12] Federal grants are often not available for these tribes as a result of the jurisdiction transfer. At the same time, PL-280 states cannot tax tribal lands to cover the costs of policing. Tribes thus have few options since they were also cut off from funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs[13] and the state government under PL-280. TLOA aimed to provide a solution to the problem by allowing tribes to opt for federal jurisdiction and thus be eligible for federal funding, but very few of these requests have been accepted.

A 2016 Senate Indian Affairs Committee roundtable about the implementation of TLOA provides insight into the problem. Almost all panelists discussed the lack of resources and its impact on their ability to implement the Act. The lack of programs for substance abuse was identified as a particularly large problem. Most areas do not have the money for anything except jailing those that need recovery programs, which further perpetuates the cycle of abuse.[14]

The chairman of the Hoopa Valley Tribal Council, the largest tribe in California, provided testimony about Hoopa’s difficulties with the Act. For many years, Hoopa had a cross-deputizing agreement with the Humboldt County Sheriff that was successful in allowing tribal officers to enforce state law against non-tribal members. Hoopa, however, relied upon the sheriff’s willingness to continue the arrangement. When a new sheriff terminated the agreement, tribal police officers lost most of their authority. The tribe was hopeful that their appeal for concurrent jurisdiction with federal authorities would be accepted and provide them with a more stable form of jurisdiction. No action had been taken by the Justice Department at the time of the roundtable.[15] The Hoopa application was finally accepted in late 2016 and was slated to go into effect in late 2017.[16] An application is supposed to take about five months to approved or denied. The Hoopa Valley Tribe waited for over two years for their application to be approved even after the cross-deputizing agreement was terminated, leaving the tribe in a state of limbo and with highly restricted enforcement abilities.

SECTION III: DATA AND METHODOLOGY

While certain aspects of TLOA were applicable for all tribes, those with individual courts and tribal police forces were affected the most by the parts of the Act this paper analyzes. One of the largest problems the Act aimed to address was communication between tribal and local authorities. If no tribal law enforcement entities existed, many changes listed in the Act would not be relevant since there would be no jurisdictional conflict between tribal and local authority and courts would not need to reform any of their practices to follow TLOA standards. This study chose to focus on California, as it has the largest Native American population of the 50 states and has a wide geographical spread that makes it fairly representative. A full list of the tribes chosen is available in the appendix. The study found data on tribes within California with these courts and police forces by contacting county sheriff’s departments. Crimes taking place on reservations were reported to their respective sheriff’s department, making the sheriffs’ the best option for finding consistent crime reports. Sheriff’s departments are available for response and generally have departments dedicated to crime reporting, while the same resources were not always available for tribal police forces. While most departments were highly accommodating, others could not be reached for comment and those tribes, unfortunately, had to be omitted from the study. Data was collected for 23 tribes out of the 40 identified for their courts or police departments. There are 109 federally recognized tribes in California.

The study looked at three specific years: 2009, 2012, and 2015. This covered the times immediately before and after the Act was passed in 2010, as well as the most recent year for which reliable and complete data was available. In an email or phone call to the sheriff, I asked for data from these three years, specified the tribes whose crime data I was looking for, and the categories of crime I was interested. The category was based on the FBI’s Crime in the United States report, which all sheriffs and police departments are required to report to. The crimes examined include arson, assault, burglary/breaking and entering, homicide, larceny/theft, motor vehicle theft, rape, and robbery. Some sheriffs also voluntarily provided information on narcotics and fraud. The San Diego Sheriff’s Department separated casino and general reservation crime as well.

General trends were examined by looking at yearly totals for crimes and examining which crimes generally saw increases or decreases in crimes. Fraud and Narcotics arrests are occasionally mentioned but these charges generally have a smaller sample size since not all sheriff’s departments provided those statistics.

SECTION IV: RESULTS

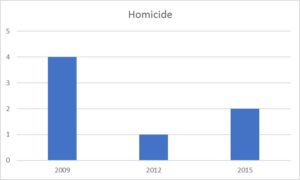

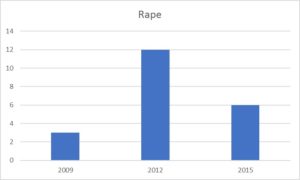

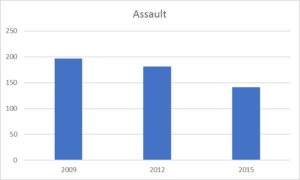

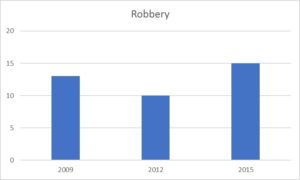

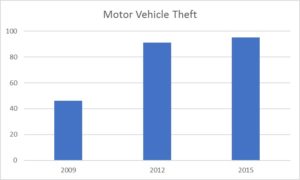

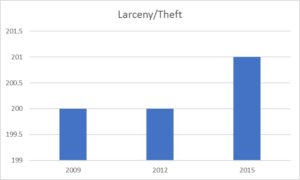

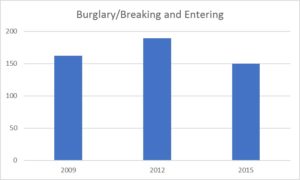

The data available thus far is not characterized by particularly strong trends. Many crimes had spikes in 2012 with either small increases in 2015 or small decreases, with variation depending on the crime type. Some violent crimes (homicide, assault, and robbery) generally saw decreases after the Act was passed. Rape, however, does not follow the same trend and actually spiked in 2012 and decreased in 2015.[17] Property crimes (arson, burglary/breaking and entering, motor vehicle theft, and larceny/theft) generally increased from 2009-2015. It is also worth noting that there were two major changes in federal law that might be affecting the data. First, in 2012, the FBI announced that they would be using an expanded definition of rape that would include a wider variety of sex offenses. The new definition was put into effect in 2013. Second, two changes in sentencing and incarceration took place in California within the data collection period. Prison realignment in 2011 shifted a large portion of the prison population to county jails while Proposition 47 in 2014 recategorized many felonies as misdemeanors. Both of these external changes may have impacted the data collected.

Summed totals of each offense per year are pictured below:

Violent Crimes

Property Crimes

The sample size used in this project was fairly limited and focused on a specific group of tribes, but the data is useful as a case study of implementation in California. There was not a consistent downward trend for these reservations over the six-year period examined which could potentially be due to the flaws in the Act mentioned earlier in the paper. An alternative hypothesis could be that there is simply increased crime reporting and enforcement, giving the appearance of an increase in crime. More reporting and enforcement will eventually lead to a decrease in crime.

These results are far from conclusive, but they are telling about one of the biggest problems with TLOA—authorities and researchers have no way of empirically knowing whether the Act is working or failing. Anecdotal evidence, as provided in Section II, is useful for getting a general idea of what still needs to be done but data provides a specific gauge to measure improvement. While these data were far too limited in scope, they can hopefully provide a basis for future research.

CONCLUSION

While the Tribal Law and Order Act was an important milestone in recognizing tribal sovereignty and took important steps towards combating crime on reservations, there is still considerable work to be done. Tribes and government agencies have raised concerns about respect for traditional justice systems, funding, and sufficient federal and state action. Statistics on crime after the Act have been slow to be published by government agencies, making it difficult to conduct quantifiable research on the Act’s successes and failures. While this project aimed to analyze some of the major problems that have arisen, it is by no means comprehensive. Future research ought to be conducted on crime outside of the limited sample size this project examined and verify if these trends will hold constant over a longer period of time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

California. California Tribal Court-State Court Forum. Native American Research Series: Tribal Justice Systems. June 2012. http://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/TribalJusticeSystemRU.pdf.

California. California Tribal Court-State Court Forum. Tribal Court-State Court Forum Meeting. June 9, 2016. http://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/forum-20160609-materials.pdf.

California. Tribal Court-State Court Forum. Jurisdictional Issues in California Regarding Indians and Indian Country. May 2015. http://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/Jurisdiction_in_California_Indian_Country.pdf.

Dimitrova-Grajzl, Valentina, Peter Grajzl, and A. Joseph Guse. “Jurisdiction, Crime, and Development: The Impact of Public Law 280 in Indian Country.” Law & Society Review 48, no. 1 (2014): 127-60. doi:10.1111/lasr.12054.

Fortin, Seth J. “The Two-Tiered Program of the Tribal Law and Order Act.” UCLA Law Review 61, no. 88 (2013): 88-109.

Hermes, Ed. “Law & Order Tribal Edition: How the Tribal Law and Order Act Has Failed to Increase Tribal Court Sentencing Authority.” Arizona State Law Journal 45 (Summer 2013): 675-701. LexisNexis Academic.

H.R. 725, 111 Cong. (2010) (enacted).

Lee, Tanya H. “Tribal Law and Order Act Five Years Later: What Works and What Doesn’t.”

Indian Country Media Network. March 08, 2016. Accessed January 22, 2018. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/politics/tribal-law-and-order-act-five-years-later-what-works-and-what-doesnt/.

Romney, Lee. “In Humboldt County, Tribe Pushes for Bigger Law Enforcement Role on Its

Lands – LA Times.” Los Angeles Times. October 20, 2015. Accessed January 22, 2018. http://beta.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-tribal-law-enforcement-20151020-story.html.

Times-Standard, Hoopa Valley Tribe. “Hoopa to Receive Federal Criminal Jurisdiction.” Eureka

Times-Standard. November 15, 2016. Accessed January 22, 2018. http://www.times-standard.com/article/NJ/20161115/NEWS/161119892.

The United States. Bureau of Tribal Assistance. Enhanced Sentencing in Tribal Courts: Lessons Learned from Tribes. By Christine Folsom-Smith. January 2015. https://www.bja.gov/Publications/TLOA-TribalCtsSentencing.pdf.

The United States. Tribal Law and Order Commission. A Roadmap for Making Native America Safer: Report to the President and Congress of the United States. By Troy A. Eid, Affie Ellis, Tom Gede, Carole Goldberg, Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, Jefferson Keel, Ted Quasula, Earl Ralph Pomeroy, III, and Theresa Pouley. Washington, D.C.: Indian Law and Order Commission, 2013.

The United States. U.S. Department of Justice. Indian Country Accomplishments of the Justice Department, 2009-Present. June 2, 2016. https://www.justice.gov/tribal/page/file/4 52541/download.

The United States. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Tribal Crime Data Collection Activities, 2016. By Stephen W. Perry. July 2016. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/tcdca16.pdf.

The United States. U.S. Department of Justice. Indian Country Investigations and Prosecutions. 2014. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-releases-second-report-congress-indian-country-investigations-and.

U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Indian Affairs. The Tribal Law and Order Act Five Years

Later: How Have the Justice Systems in Indian County Improved. 114th Cong., 1st sess., December 2, 2015.

APPENDIX A

| Tribe | Contact |

| Table Mountain Rancheria of California | FBI’s Uniform Crime Report—Tribal Agencies |

| Yurok Tribe of the Yurok Reservation | FBI’s Uniform Crime Report—Tribal Agencies |

| Morongo Band of Mission Indians | County Sheriff– Riverside |

| Pechanga Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the Pechanga Reservation | County Sheriff– Riverside |

| Chamehuevi Indian Tribe of the Chemehueivi Reservation (2016, not 15) | County Sheriff– San Bernardino |

| Colorado River Indian Tribes of the Colorado River Indian Reservation (2016) | County Sheriff– San Bernardino |

| Jamul Indian Village of California | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Viejas Band of Mission Indians | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Rincon Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the Rincon Reservation | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| San Pasqual Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of California | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Sycuan Band of Kumeyaay Nation | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| La Jolla Band of Luiseno Indians | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Pauma Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the Pauma & Yuima Reservation | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Mesa Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Mesa Grande Reservation | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Los Coyotes Band of Cahuilla and Cupeno Indians | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Barona Band of Mission Indians | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Pala Band of Mission Indians | County Sheriff—San Diego |

| Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians | County Sheriff– Riverside |

| Campo Band of Diegueňo Mission Indians | FBI’s Uniform Crime Report—Tribal Agencies |

| Ewiiaapaayp Band of Kumeyaay Indians (Cuyapaipe Reservation) | FBI’s Uniform Crime Report—Tribal Agencies |

| Washoe Tribe | County Sheriff– Alpine |

| Table Mountain Rancheria of California | FBI’s Uniform Crime Report—Tribal Agencies |

[1] Seth J. Fortin, “The Two-Tiered Program of the Tribal Law and Order Act,” UCLA Law Review 61, no. 88 (2013): 91-92.

[2] Ibid. 91.

[3] United States, Tribal Law and Order Commission, A Roadmap for Making Native America Safer: Report to the President and Congress of the United States, by Troy A. Eid, Affie Ellis, Tom Gede, Carole Goldberg, Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, Jefferson Keel, Ted Quasula, Earl Ralph Pomeroy, III, and Theresa Pouley (Washington, D.C.: Indian Law and Order Commission, 2013), 11.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Fortin 92.

[6] Fortin 95; H.R. 725, 111 Cong. (2010) (enacted) 23.

[7] Ibid. 4

[8] Ed Hermes, “Law & Order Tribal Edition: How the Tribal Law and Order Act Has Failed to Increase Tribal Court Sentencing Authority,” Arizona State Law Journal 45 (Summer 2013): 690, LexisNexis Academic 690.

[9] Fortin 108.

[10] Valentina Dimitrova-Grajzl, Peter Grajzl, and A. Joseph Guse, “Jurisdiction, Crime, and Development: The Impact of Public Law 280 in Indian Country,” Law & Society Review 48, no. 1 (2014): pg. #, doi:10.1111/lasr.12054.

[11] This is because tribes usually constitute a small portion of the county’s total population, and thus the reservations are too small to identify within crime statistics. While most cities are individually reported for the FBI’s UCR report, reservations are a part of the county and thus are not individually reported.

[12] U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Indian Affairs, The Tribal Law and Order Act Five Years Later: How Have the Justice Systems in Indian County Improved, 114th Cong., 1st sess., 2015.

[13] Lee Romney, “In Humboldt County, Tribe Pushes for Bigger Law Enforcement Role on Its Lands,” Los Angeles Times, October 20, 2015, accessed January 22, 2018, http://beta.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-tribal-law-enforcement-20151020-story.html.

[14] U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee, The Tribal Law and Order Act Five Years Later.

[15] Ibid. 43-45.

[16] Times-Standard, Hoopa Valley Tribe, “Hoopa to Receive Federal Criminal Jurisdiction,” Eureka Times-Standard, November 15, 2016, accessed January 22, 2018, http://www.times-standard.com/article/NJ/20161115/NEWS/161119892.

[17] In 2012, the FBI announced that they would be using an expanded definition of rape; however, this new definition did not go into effect until 2013.